- Home

- Janine Armin

Toronto Noir Page 2

Toronto Noir Read online

Page 2

“I’m lost, but I’m making record time.”

—Allan A. Lamport, Mayor of Toronto

During the summer of love, Toronto was filled with kids who’d hitchhiked to Toronto to get stoned in Yorkville and enjoy a little loving wherever they found it. One steamy Sunday, Billy and I were walking through Queen’s Park. As always, someone in the crowd was playing a guitar badly and the sweet smell of pot was heavy in the air. The lawns were littered with sleeping bags where girls with sunbursts painted on their cheeks and dreamy unfocused eyes were pressing their bodies against jean-clad barefoot boys with straggly beards. Billy stepped over them as if they were excrement.

We’d just passed the statue of Edward VII on his horse, when I tripped over a boy in a sleeping bag and lost my footing. Billy caught me before I fell, but the boy rolled over lazily, gave me the look boys give girls, and patted the place beside him on the sleeping bag. In a flash, Billy dropped to his knees and began to pummel the boy. When I heard the sound of fist against bone, my stomach heaved, but I managed to pull Billy back, and he pushed himself to his feet. For a beat, Billy and I stood side by side, looking down at the boy as he felt his jaw. I was sure there’d be trouble, but the boy just smiled and flashed us the peace sign.

For some reason, the gesture enraged Billy. The blood drained from his face and he aimed a kick at the boy’s leg. “That’s right, asshole,” he said. “Peace and love.”

Some of the other kids were emerging from their sleeping bags, rubbing their eyes and trying to get their heads around what was going on. Billy’s wiry body was a coiled spring.

“Keep it up, you sorry little pieces of shit!” he yelled. “The more you smoke and screw, the more useless you become. And that works for me. You don’t know who I am, but I know who you are. Every day I serve your fathers their lunch. While you’re lying in parks getting crabs and blowing your minds, your fathers are transforming this city from Toronto the Good into Toronto the Great. Go ahead and laugh, but you’re the reason I’m going to be part of Toronto the Great. You want to know why? Because you’re breaking your fathers’ hearts. You’re the reason they order double martinis every day and get loose-lipped about the projects that are going to change this city forever.”

The jaw of the boy Billy hit was starting to swell, but he kept the faith. It was an effort for him to form the words, but he managed. “Chill, brother,” he said.

Billy shot the boy a look of pure hate. “Fuck you,” he said, then he grabbed my hand and dragged me after him out of the park.

“If I had $1,000,000 I’d be rich.”

—Toronto musicians The Barenaked Ladies

Billy was silent till we got to Bloor Street. “Are you okay?” I said finally.

When he turned toward me, there was a new darkness in his eyes. “Yeah, I’m okay. I’m more than okay. I’m terrific. I deserve to make it. When Toronto’s a world-class city, I should be one of the kings. I’m smart. I’ve got drive and I’ve got nerve. The only thing I don’t have is money.” His voice broke, and for a terrible moment I thought he was going to cry. “I know where this city is headed. And I’ve got plans—great plans—I just don’t have the money to get started. And that means I’m fucked.”

“You can save,” I said.

“From what I earn at Winston’s? Fuck!” He laughed. “Only one thing to do. Wait for Vova to die.”

“What would that change?”

His laugh was short and bitter. “I’m in Vova’s will. It’s supposed to be a big secret, but I’m the heir. Vova lost touch with his people in Russia years ago. He says they’re probably dead by now. Anyway, one night when he got drunk, he started obsessing about how the government was going to take his house after he died. I told him that if he had a will, the government couldn’t touch his property. So he poured himself another shot and wrote out a will leaving everything to me.”

“How come you never told me?”

“Because I made a promise to Vova.” Billy’s voice was suddenly weary. “Also because it doesn’t fucking matter. Vova has the heart of an ox. He’ll live to be a hundred.”

“He drinks a lot.”

Billy shook his head. “Yeah, maybe I’ll get lucky, and some Saturday night he’ll get loaded and walk under the wrong ladder.”

“Things work out for the best,” I said, but for once my mind wasn’t on Billy’s future. It was on my own. My period was three weeks late, and as a rule, I was regular as clockwork.

“Come in and get lost.”

—Slogan of Honest Ed’s Discount House,

Bloor and Bathurst

Years later, when my son came home from school and told me that the flapping of a butterfly’s wings can cause a chain of events that ultimately causes or prevents a tornado, I thought of the summer of 1967, when the flapping of the wing of a single butterfly in Russia changed four lives in Toronto.

By the time the Canadian National Exhibition opened at the end of August, I still hadn’t told Billy we were going to have a baby. For days, his mood had been as sullen as the weather. He had a line on some land north of Toronto that was going cheap, but the regular customers at Winston’s were on holidays, and tips were down. For the first time since he came to the city, Billy had been forced to dip into his savings to make ends meet, and his anger was building. I could see it in the set of his jaw and in the new fierceness of his temper. When I suggested we forget our troubles by spending an evening on the midway, he tensed and balled his fists. I flinched, and Billy saw my fear and gave me a melting smile.

“Okay, babe. Tomorrow’s Saturday. I’ll have my Saturday night drink with Vova—got to keep on his good side. Then after I pour him into bed, we’ll go to the Ex. We’ll eat some cotton candy. I’ll win you one of those fancy satin dolls on the midway; then we’ll take in the fireworks. Good times!”

Good times. But for Billy and me, good times always carried a price. The next day, when I came home from work, Billy was waiting for me on the front steps. He was ashen. As soon as he spotted me, he grabbed my hand and dragged me away from the house.

“My fucking luck,” he said, his voice cracking. “I answered the phone today when Vova was out doing errands. It was long distance, and I couldn’t make out what the person on the other end was saying. We yelled at each other for a couple of minutes trying to make one another understand, then somebody who said he was Vova’s nephew came on the line. His English was excellent. He told me that he was crying with happiness to finally locate his uncle, because he had found a way to get to Canada and be reunited with Vladimir Maksimovich. So that’s that. The nephew comes to Toronto. He gets the house, and I get the shaft. My fucking luck.”

Billy was as low as I’d ever seen him, so I did what girls in the movies did when their men were down. I put my arms around him and murmured encouragement. “You always tell me people make their own luck,” I said.

I was a naïve nineteen-year-old trying to make the man I loved feel better, but my words transformed Billy. It was as if I’d ignited a fuse in his brain and the possibilities were shooting forth. He pounded his fist into his hand. “You’re right. We make our own luck.” His eyes were burning, absorbed in a vision that only he could see. He grabbed me by the shoulders. “Babe, you’re going to have to make yourself scarce for a while.”

“What about the fireworks?”

“We’ll make it in time for the fireworks. I promise you.” His grip on my shoulders tightened.

“Billy, you’re hurting me.”

“If we don’t do this right, you’re going to be hurting a lot more. Now don’t ask questions. Just follow instructions. Go up to your room, stay there, and listen for the phone downstairs in the hall. If it rings, grab it—quickly. Tell whoever it is that Vova’s not here.”

“But if you and Vova are in the kitchen, he’ll hear the phone.”

“I’ll put the radio on the crazy station that plays Russian music and crank it up.”

“Billy, what are you going to do?”

/>

He shrugged and gave me a sly smile. “Same thing I do every Saturday night—have a drink with my pal, Vova.”

“Toronto will never be the same again.”

—Phil Givens, Mayor of Toronto

I did what Billy told me to do. I went to my room, opened the window, and sat staring into the sultry twilight, listening. The weekly drinks were a ritual. Vova never opened a bottle until Saturday night, and then he drank till the bottle was empty. Billy’s job was to pour the vodka, listen, and get Vova safely into bed. It never took long. Vova put in long hours, and he drank fast. That night, I could hardly breathe as I listened to the mournful tunes of Russian radio and the voices of the two men: Billy’s baritone, playful, deferring; Vova’s bass, booming louder as the level of the bottle dropped. Our landlord’s conversational topics were limited: his hatred of all government; his contempt for rules and regulations; his pride in his selfreliance and accomplishments. As I heard the familiar litany, I relaxed. It was just another Saturday night, after all. Then the phone downstairs in the hall rang, shrill and insistent, and my heart began to pound. I raced to answer it. It was long distance. I broke the connection, and left the phone off the hook. In that instant, I knew that nothing would ever be the same again.

The kitchen door was closed. I crept down the hall and opened it a crack. Vova and Billy were sitting at the kitchen table. Vova was slumped over the table, his broad back toward me. Billy looked up when the door opened. I nodded, and Billy stood, went to Vova, dragged him from his chair, and began moving toward the basement stairs. The old man came to and started grumbling. “What the hell?”

“Time for bed,” Billy said, coolly.

Vova laughed. “Hey, you make mistake. That’s the basement way. What the hell? I’m the drunk one.” He laughed again; then Billy pushed him. For a beat there was silence, then a dull thud as Vova’s body hit the concrete at the bottom of the stairs. Billy disappeared after him. Mesmerized, I moved across the kitchen floor to the door that led to the cellar. I saw it all: Vova’s body splayed on the floor, twitching like a grotesque abandoned puppet; Billy sitting back on his heels, breathing hard and watching. When the twitching didn’t stop, Billy leaned forward and pinched Vova’s nostrils shut until finally he was still. As Billy came back up the stairs toward me, I felt a wash of relief; then his fingers were around my throat. The stench of death and rage that poured off his skin was overpowering.

“If you tell anybody what you saw, I’ll kill you,” he said. And I knew he would.

Billy was a man who kept his promises—all of them. That night, as Vova lay dead in the basement, Billy took me to the fireworks at the CNE. As the rockets ignited and threw Billy’s profile into sharp relief, he was so beautiful I couldn’t imagine my life without him. But the moment passed. The last exploding star arced across the sky, and the dark, cheerless night closed in on us. Coming home on the subway, we leaned against each other, exhausted by the events of the day. The house on Charles Street West was silent, and like children in a fairy tale who suddenly find themselves in peril, Billy and I held hands as we climbed the stairs. That night Billy made love to me with a violence that thrilled and terrified me. When he was through, he fell away like a sated animal and slept the sleep of the innocent.

I didn’t sleep. I couldn’t. My mind was assaulted by images that I knew not even time could erase, and I was terrified that I might have, somehow, harmed my baby. When Billy’s breathing became deep and rhythmic, I slipped out of bed and started for the door. Obeying an impulse I didn’t understand, I took the shoebox that contained the spiral notebooks Billy had filled with his plans and ideas. Then I went to my room, packed my suitcase, and walked out the front door of the house on Charles Street West for the last time.

It’s always been easy for a woman to disappear in Toronto, especially if no one really wants to find her. The day after I left Billy, a childless widower in his late fifties hired me as his companion/housekeeper. Six weeks later I married him. When my son was born, I named him after my new husband: Mark Edward Lawton.

My husband was a generous and loving father, but naming a child after a man does not make the baby that man’s son. From the day he was born, Mark was Billy’s boy. As I knelt on the floor of my bedroom closet and pulled out the shoebox that held the spiral notebooks in which Billy had recorded his dreams and secrets, I knew that Billy’s boy needed his dad.

“It’s my city. I don’t have to consult anyone.”

—Mel Lastman, Mayor of Toronto

I didn’t go downtown often. I could buy everything I needed on the Danforth; besides, when I got off the subway at Bloor, I felt lost. Nothing stayed the same. It was as if a sorcerer who was never satisfied had taken over the old neighborhood, replacing the solid brick houses and tiny lawns with buildings that soared and shone brightly until the sorcerer waved them away and conjured up buildings that soared even higher and shone even more brightly.

It must be hard to keep focused in a world that’s constantly shifting. Perhaps that’s why Billy, in a gesture that the Toronto Star praised, located his offices on the site of the house that Vova left him. I thought I would feel a pang when I returned to the place I had run from in the early hours of that hot night of love and death. But I felt nothing. The sleek shops and gleaming high-rises that lined Charles Street West made it so uniformly perfect that there was nothing left to recognize.

Billy’s office was on the fifty-first floor. I was counting on the elevator ride to give me time to compose myself, but the smooth soundless glide was over in seconds, and when the doors opened, I found myself in Billy’s world. The reception area of Merchant Enterprises was designed to impress and intimidate: Everything was hard-surfaced, sharp-edged, and high gloss. The woman behind the reception desk fit right in. Whippet-thin, porcelain-skinned with red-red lips and red-red nails, her close-fitted sharkskin suit had been cut to showcase her perfection. She gave me a quick, assessing look, decided I wasn’t worth her time, and glared. When I asked to see Billy, she was brusque, almost rude. “Mr. Merchant isn’t available.”

“May I leave something for him?”

She nodded.

I pulled the spiral notebook from my purse, ripped out a page upon which Billy had written the words KILL VOVA a dozen times in the margins, and handed it to her. “Give this to Billy,” I said. “Tell him it’s from the woman who was standing beside him in the picture in the paper this morning.”

She held the grimy ripped page between her thumb and forefinger and looked at it with distaste.

“Better get a move on,” I said.

She narrowed her eyes at me, decided I meant business, and then pressed a button with one of her perfectly shaped nails. “Mr. Merchant, there’s a person here to see you. Her picture was in the paper with you this morning.”

“Nicely done,” I said. Then I sat down to wait. Time-wise, Billy’s sprint from his office to the reception area must have been a personal best, but he wasn’t even breathing hard. He looked me up and down, gave me his bullet-stopping grin, and held out his arms. “It’s been a long time.”

When I didn’t walk into his embrace, Billy turned to his receptionist. “Nova, cancel the rest of my appointments for this morning and hold my calls.” He placed his fingertips on my elbow. “Why don’t we go down to my office? I have a feeling you and I’ve got a few things to discuss.”

We were silent as Billy guided me down the hall, opened the door, and led me inside. For the first time since he’d spotted me in the reception area, Billy seemed uncertain. “I didn’t think I’d ever see you again, but you’ve always had a way of surprising me.”

“I’m not through yet,” I said. Two walls of Billy’s office were floor-to-ceiling glass, and the view of the city was spectacular. For a few moments, I looked down on Toronto, getting my bearings.

“So what’s the verdict?” Billy asked.

“It’s a great city,” I said. “But you always knew that, didn’t you?”

“Ye

ah, and from up here you can’t smell the garbage.”

There was something different about Billy that I couldn’t put my finger on. Up close, there was no doubt that his hair was dyed, and the skin around his eyes had the strange tightness that comes from too much plastic surgery. But the change in Billy was more than cosmetic. Underneath the thousanddollar suit, there was a weariness that no amount of tailoring could disguise. And his voice was different—lower and flatter. It didn’t take long for the truth to hit me. For the first time in his life, Billy Merchant had stopped looking forward to the future. There were no more mountains for him to climb. Billy met my gaze. “Time marches on, eh?”

“Yes,” I said. “Time marches on.”

“You don’t look half bad for an old broad.”

I laughed. “Still a charmer.”

“So shall we cut to the chase?” Billy examined the paper I’d ripped from his notebook. “Kill Vova,” he said. His laugh was short and bitter. “Do you know I truly don’t remember writing those words?”

“You think I faked this?”

He shook his head. “No, that’s my handwriting. And I’m assuming there’s more where this came from.”

“You’re right. The morning I left, I took your notebooks with me. Anyone who wants to know the real story of the King of Charles Street West would find those notebooks very valuable.”

Billy’s gaze didn’t waver, but as he pulled out his checkbook and pen, his hands were shaking. “You’re not capable of pulling this off,” he said quietly. “There are two kinds of people in the world: the ones who betray and the ones who get betrayed. If you were going to betray me, you would have done it long before now.” He tried a smile. “That doesn’t mean you’re not going to get a payoff. You deserve something for keeping quiet all these years. So who do I make the check out to?”

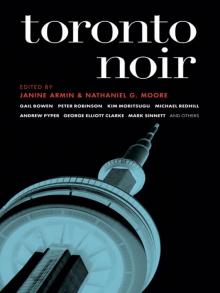

Toronto Noir

Toronto Noir