- Home

- Janine Armin

Toronto Noir Page 8

Toronto Noir Read online

Page 8

Miguel, their tour guide, was such a man. Short and compact in body, barrel-chested, with a few uneven black sprigs of hair for a beard, he had a thin, rosy scar along his jawline and the haircut of a more urban, moneyed man. When he smiled, Beth noted his strong, small, pointy teeth.

This was in a café in Lago Agrio, way-station for travelers, frontier town for the desperate and entrepreneurial. She and Paul had been waiting a long time on a patio, clinking their cups of Nescafé against their saucers.

“Do you think that’s him?” Paul pointed toward the street, where a mocha-skinned man was pulling a trolley. They were to expect a guide who spoke five languages, a war veteran, friendly and “uninhibited,” the keen teenager who booked their trip had reassured them. When Miguel appeared it was from within the rendezvous restaurant; his arms made his T-shirt bulge with their baseball-sized biceps and he was sporting cheap orange flip-flops, which he continued to wear for the duration of the journey, exposing his long, yellowy-tough toenails, and making the rest of the tour group, in their beige, super-tread hiking shoes, feel subtly, wonderfully mocked.

On the bus to the oversized, motorized canoe, which was to take them to their campsite, the dust from the window made Beth cough, and the rutted roads caused the bus to jump. The inside of her head was all jangly with priorities and survival, and she felt sunburned although she had not been in the sun. She nodded to the two Germans who had joined the group, and then pushed past Paul, who was sleeping, a thin line of spittle reaching from his bottom lip to the strap of his day pack, which he had, wary of pickpockets, left attached to his back.

“Do you mind?” She motioned to the vacant aisle seat next to Miguel.

“Not at all,” he said. “You are welcome.”

She sat next to him, not speaking, trying to catch her breath.

“You are having some difficulty, some respiratory difficulty?” He turned toward her, face creased with concern and something else—amusement or maybe lust?

“I’m fine,” she said, and took in a big lungful of air, right down into her diaphragm, as she’d learned in a few yoga classes and tricky situations.

“Good,” he said and went back to his book.

Beth closed her eyes, but that made her dizzy, so she opened them. It was difficult, sitting on the aisle, to find a place to look. Straight ahead meant a row of seatbacks, brown vinyl and grimy. It meant absorbing the reality of the interior of the bus, a rollicking, wretched press of passengers, bulky bags, boxes, and bound chickens. It meant considering which qualifications, exactly, were required to drive a bus in this strange country. And looking outside, well, that would involve craning over Miguel to the window so that her head was positioned directly above his crotch.

Also, Beth was experiencing traveler’s terror—the pervasive notion that each moment represented a small treasure trove of noteworthy difference, of sights, sounds, smells completely and utterly foreign to what she had ever encountered, and that she would never pass this way again. She pivoted her body and her breast grazed Miguel’s arm. She muttered an apology, and squinted out at the side of the road. Outside was both hazy with dust and excessively green. The foliage looked prehistoric—gigantic ferns bowing chaotically to the palms reaching high up into the cloudless sky. This was it—the jungle. Miguel shifted to turn the page of his book and she felt obliged to speak. “What are you reading?”

He closed the book to show her the cover, a sepia-toned watercolor of a barn with a fair-haired woman standing in the foreground looking to the horizon. In the top right-hand corner of the book was a gold seal. Beth peered at it. It was one of Oprah’s book club picks. Miguel was watching her.

She had no idea what to say. The man in the tour agency had told them Miguel still had a bullet in his thigh from fighting in the border dispute with Peru. Finally she settled on, “Any good?”

Miguel nodded eagerly. “Very good, and it helps me to practice, to stay fluent, use new words.” He opened the book to the page he was on. “What does this mean?” He pointed to a word.

Beth did not know what the word meant. She took the book from Miguel and read the blurb on the back. A multigenerational saga set in the American Midwest with a complicated, malevolent patriarch at its core. “Must be dialect,” she said, shaking her head. “Sorry.”

“It’s okay.”

But she knew she had fallen in his estimation. She glanced out the window again. There were black pipes running alongside the road that seemed to be made out of the same plastic used to make heavy-duty sports drink bottles. The pipes didn’t look very serious, especially next to the profusion of vine and leaf that surrounded them. They passed a length of pipe covered in white spray paint. Beth caught the word OXY repeated in messy, angry capital letters. “What is that?”

Miguel closed his novel, placing a purple bookmark in its pages. “Oil pipelines,” he said. “My people, the people of the river, the Siona, they want the oil companies out. They’re sabotaging our home. We have stopped them before. We are well-organized, and although it is not entirely in our nature, we protest peacefully.”

“Is it true you have a bullet in your thigh?” Beth blurted, somewhat fanatically.

Miguel nodded. “My partner was not so lucky,” he said.

From across the aisle, Beth heard what sounded like a deliberate sniff from Paul. Perhaps it was warranted. But she was mesmerized by Miguel’s offhand manner, his apparent obliviousness to his own glaring, gaudy contradictions.

She wondered where Miguel was now, envisioned him paddling valiantly, hopelessly through the unthinkable sludge his river had become. Or maybe not. Instead: in a hotel room in town, his head between the legs of one of the other “uninhibited” citizens of El Oriente. The women of Lago Agrio had been as colorful and intent as the jungle birds; their tight green leggings, pink stilettos, and bands of quivering exposed flesh spoke mostly of joy and heat.

Paul was speaking to her, saying something about the political situation in South America. “It was Occidental, Beth. You know, the one they’ve been protesting for years. Here, then, is irony. Finally, they get them to admit their free trade has been anything but. They manage to oust them from the land, to reclaim what is theirs. And then, this. I wouldn’t be surprised if it’s the Man simply asserting his dominance. Oops, spilled some oil in your fresh, piranha-infested, life-giving waters. Sorry about that, but you shouldn’t have asked us to leave so rudely. We were, after all, your guests. And were we not gracious? Did we not give your people training and jobs? Oh, we know. The rule of law. But what about the rule of the jungle?” Paul was clicking around the website as he spoke, searching madly for clues.

She still could not quite grasp what he had shown her. There were ramifications, she knew, delicate ecosystems, butterflies on one side of the world flapping their diaphanous blue wings, while on the other side lucky humans sampled sushi; everything explained by a near-invisible knotted string you could follow back to a few greedy men with polished scalps and eyes like hunks of coal dreaming of the ninth hole and profit charts that explained their own lives to them in triplicate.

And then panic pushed like a spring shoot through the loam of her thoughts. She remembered Miguel, as she had been remembering him suddenly and without apparent justification, since she returned to her house on Willard Avenue with her husband of thirteen years, in the west end of Toronto, here amidst some tall buildings, next to a river and a lake, where she lived and would maybe die. Since childhood she had pinned herself to this map. It reassured her to know the order of her own locale. She knew the earth did not belong to her but to her grandchildren, and perhaps not even to them. But what if there were no children, no grandchildren, and the generational link was lost? One day she would be old, bereft, still angry … The image of that other equatorial river she had also begun to call her own, lying like a dark, drugged serpent, flashed into her mind. She turned to Paul. “I’m going to the river.”

“I’ll follow,” he said, with a knowing, almost

servile condescension.

She shrugged, thought for a moment about what she might need, then shrugged again. She took Colbeck Street over to Jane, held out her hand at the crosswalk, then marched across like a trusting fool. From there it was a short hike down to the entrance of the park, and down the short steep hill at Humberview Road, and the longer sloping hill of Old Mill Drive. She reached the parking lot running, had to stop and crouch to catch her breath. The day was overcast and humid; she could feel the threat of rain in her sinuses. The scattered copses of trees and fertile patches beneath the bridges had the look of hiding places for humans. It was the sort of day bad men chose to bury body parts.

Paul caught up with her. She turned for a moment to look into his familiar, fretful face. He was stuttering out facts like a telegraph machine: “You know, it’s Petro-Ecuador now. The Ecuadoreans managed to wrest back control, but only after a long and underhanded battle. It was the Americans first. Occidental. They were the ones who invaded what was essentially forbidden territory. And then they did sneaky things like sell part of their shares to EnCana, a Canadian company, Beth, who then sold to the Chinese. If you think we are blameless in all of this you are wrong. We Canadians drift in on the Americans’ wake. Oil or diamonds—it doesn’t matter, we’ll take their sloppy seconds with our shadowy lesser dollar.”

She scrambled her way down the concrete wall that had been built to counter flooding, found a log designed for sitting, and looked toward the stone bridge, the site of the Old Mill, its ruins pressed up against a new spa and condos. A fisherman was standing under the bridge, his hip waders making him large and mournful. He baited his hook, cast into the deeper waters downstream, and hooked a salmon while Beth watched. In the fall, the salmon would be running thick through these waters, leaping with every ounce of their life force to clear the man-made steps that had been installed to control the flow of the river. Their connection to their home, to their little patch of earth and rock and water, was that compelling, that terrifying and true.

The water was higher than it had been for weeks; there had been fierce, unseasonal rains while they were away, then in late July the sun had come out and the river had receded, but the most recent downpour had lifted it once again. Above them, a subway train went rumbling by. Out of the corner of her eye, Beth saw a small black airborne shape, a scrap of red. And there it was: familiar, dogged by its Ecuadorean shadow, its strange tropical double. Here—a red-winged blackbird darting out. And there—a toucan decimating a small hard fruit with its unlikely beak. Here—a pair of squirrels trapezing through the low branches of a maple. There—a monkey grooming his mate, bold and fastidious, perched on his very own Amazonian awning.

Paul tapped her shoulder. “Let’s not stay here, Beth.”

He didn’t appreciate the river the way Beth did. Six months ago, four boys had mugged him and two of his friends on a Saturday night as they strolled and took turns toking like teenagers. The boys held a long serrated knife to Paul’s throat; they fancied themselves gangsters. Later, close to dawn, the police found three of the four hiding in a gully. They were peppered with red ant bites, their pockets clanking with change.

“Beth, I’m taking you home. You’re in no condition to be traipsing around down here like some goddamned explorer of yore.” He grabbed her arm.

Beth shook free, but could not remain sitting. She got up and swatted at the seat of her pants, but nothing was clinging there. She had to cut back up to the main path before she could make it down to the beaten sandy trail next to the water again. Paul zigzagged behind her, panting and driven by loyalty. On the far shore, a night heron was picking through pebbles and bits of trash. The bird stepped carefully over a soda can. Beth stopped to trail her hand in the water. At the edges, the river was lukewarm, but in the center, in the depths, it would be cold. A man had drowned here, having jumped in after his dog. The dog survived.

That first night in the jungle, she and Paul had huddled close on their mattress, flicking the flashlight on and off like schoolchildren, peering out through the mosquito netting at the matte surface of the night and the six other gauzy, tented sleeping areas.

“They’re like bridal beds, aren’t they?” Beth said.

“Or ghost ships,” Paul replied, and Beth turned to him, surprised. They kissed then, softly shocked kisses that helped them both to sleep, despite the rustlings, the constant exchange of information and emotion under the canopy, despite the scurrying geckos and dazed spiders Miguel had warned them might come tumbling from the rafters. Despite their recent history and despite themselves, they kissed and slept like gentle dragons, until the clear commands of the camp cook woke them.

And then there was the issue of moving from sleep to waking, selecting the appropriate attire without parading around as God and all of nature had intended. Paul managed to pull on a pair of shorts and wriggle a T-shirt over his head before emerging to introduce himself to the German couple who had farted unself-consciously as the morning light crept in, and the group of cheery Spaniards sitting on the steps smoking cigarettes. Beth put on her quick-dry pants in a supine position but had to stand to do up the zipper. She ran her hands over her abdomen as had become habit. As if rubbing Aladdin’s lamp, she caressed the pouch of flesh above her belly button. She looked up because she thought she could feel Miguel watching her across the expanse of swamp that separated the sleeping shelter and the dining area, peering out toward her, silhouetted against the mosquito netting like a shadow puppet. Perhaps they all appeared this way, funny outlines backlit by their particular cultures trampling their way through the jungle, laughing and drinking around the slab of a wooden table, starting comically at all the same sights—the tarantulas waving their chubby arms, the sloths hanging like overstuffed handbags from the branches of ancient trees. Watching Miguel watch her, she was overcome by modesty; she had not yet thought to put on a shirt, and she could feel sweat beginning to accrue underneath her breasts. She reached for her bra.

It had been concluded that there was nothing technically wrong with either of them. At first Paul had scoffed, said something about natural selection, overpopulation, all for the best, and she had felt an odd pull in her gut, as if one of her arteries had gone spelunking in the region of her uterus. They had walked for two hours in High Park after the third specialist gave his verdict. It was February, the temperature was sub-zero, and they had to dodge Canada geese strutting like cops along the path. They did not speak; although the words were there, their footsteps over the snow and ice told a more complete, forlorn story. They wore parkas and Thinsulate accessories, but the wind blew straight through them. Once they had circled the park four times, Paul said, “Chicken breasts for dinner?” and Beth nodded, veering toward Bloor Street.

Beth made her way closer still to the water’s edge and began creeping along, stepping over boulders and small eddies of water. If she squinted she could almost envision it, and it took a whole concerted face scrunch to make it real. But the greenery here, for the most part, belonged along the edges of a golf course. And although the humidity approximated the freighted air of the jungle, it also brought with it an oppression unique to the lands that bordered Lake Ontario. She could hear Paul in the brush behind her and was flung back to Cuyabeno—that noisiness of humans pushing their way through chummy, crowded plants.

On the second Wednesday of the trip, the group had traveled in tiny, tippy, handmade canoes to the opposite shore, 300 meters downstream. On the way they witnessed pink river wraiths—dolphins cresting in the calm, fresh waters.

“We will visit one of my friends,” Miguel announced cryptically.

They disembarked on a small beach where sandbugs chomped at their exposed flesh. Through it all, Miguel remained serene in his orange flip-flops, smiling as they slapped at their skin, scrambling for repellent. When they looked up, sweating, he was already waving a walking stick up ahead.

“Isn’t it exciting?” Beth said to Paul. “I wonder where his friend lives. I wonder wh

at he does in here.”

“I imagine he lives his life, Beth. Just with different dining room furniture.” Paul did not react well to bug bites; his legs were covered in loonie-sized pink welts. “Besides,” he said, pointing up ahead, “I’m not sure Miguel knows where he’s going. Perhaps he is not as canny with a compass as your coureur de bois, eh?”

Beth searched for Miguel and found him wandering over a small patch of land, stopping to make peculiar bird calls, his hands cupped up near his lips. “He’s signalling,” she told Paul. “We don’t always have to resort to cell phones.”

And sure enough, within minutes, a three-tiered whistle call came sailing back. Miguel began running over the log- and mulch-strewn ground, bounding over obstacles and jumping to high-five low-hanging palm leaves.

“He expects us to follow when he’s carrying on like that?” Paul said.

But they did follow him; they had no choice. There were times when they lost sight of Miguel altogether and the two of them paused, turned to each other, fully grown Hansel and Gretel searching for signs of their own selves, the crumbs that signal a trail of existence. If not for the other members of their band, who came stumbling through the ground cover with their digital cameras outstretched, they might have believed themselves to be truly abandoned and alone.

“C’mon,” Miguel finally called to them. “We’re almost there.”

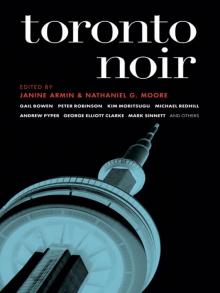

Toronto Noir

Toronto Noir