- Home

- Janine Armin

Toronto Noir Page 14

Toronto Noir Read online

Page 14

I poured her a Scotch and we toasted the future. She’d been at almost every one of the bar’s traditional music nights and boxing matches since we opened. Now her husband was standing in the middle of the room.

“Cooper didn’t do it justice,” he said.

“She was only down here once. She told me she wasn’t comfortable working off hours, even for the money I was paying.”

“Expensive to keep a secret?”

“Obviously not expensive enough.”

He walked into the room, turning slowly to take in all the details. “Looks pretty authentic.”

“I had pictures of nineteenth-century saloons to guide me. I did a lot of research. This wasn’t the only speakeasy in Toronto in 1850.”

“But it’s the only remaining one.”

“I think it must be.”

He walked among the round zinc tables toward the stage. “There’re wings?”

“Dressing rooms too.”

“Wow,” he said. “These the original floors?”

“No. They were a mess. We did these ourselves. We kept as many of the old nails as we could salvage, though. Some of it’s original.”

He walked across the front of the stage to the corner of the room where the boxing ring was. For matches, I had four men simply lift the ring and bring it into the middle of the room, where we’d arrange the chairs around it. You could break it down and put it away, but I liked the look of it, menacing and lonesome, in the corner of the room under a single light. He stood beside it, wiping his hand over the canvas. “You got a champ?” he asked me.

“Ernie Paschtenko. Russian kid. He fights out of the Cabbagetown Club, but someone brought him down to us and he’s been fighting friendlies here for a couple of years. His record is ten and one.”

“You do some training here too?”

“A little.”

“And who judges the bouts?”

“I do, with a couple of the regulars.”

“Nice,” said Albrecht. “A whole secret world, huh?”

“Until now.”

“You fight?”

“I spar once in a while, but no. I don’t got much of a chin.”

Albrecht pushed one of the ropes up and threaded himself under it onto the canvas. For a big man, he was lithe. He stood in the ring, testing the platform. “I tell you what,” he said. “I know a good thing when I see it. I’ll write this up back at the station house and say everything’s in order. But you got to promise that you’ll get a license for down here. I can’t help it if someone less inclined to see the charm of this place stumbles onto it.”

You have to do a certain amount of diminishing the missing corner of the triangle to feel in your right mind when you’re cuckolding a man. Leonard Albrecht hadn’t deserved an atom of it. He was good people, but it shouldn’t have surprised me. He’d once loved Katherine. I wondered if there was a way I could make it up to him without his knowing what I was doing. “I’ll get a license then,” I said.

“That’ll mean inspections, McEwan. So you have to put this ring away when it’s not in use. And you can’t charge admission anymore.”

“Okay.”

“You got any kind of records for your sales?”

“Somewhere.”

“Get rid of them. The day you get your license is the day this place officially opens.”

I crossed the room to the ring. “I’m grateful for this,” I said to him. “I’d be happy to put you on the list. You know, for matches and other things.”

He was pretending to fence with an invisible opponent, dodging blows, feinting left and right. “That’d be great,” he said. “I could slip in if I get a quiet shift some night.”

“You ever box?” I asked him.

“Naw, just a student of the sport. I don’t understand people who say it’s all brutality, though. It’s the most basic contest there is. Man against man, a duel of honor. My wife hates it.”

No she doesn’t, I thought. If Leonard Albrecht was planning on coming to matches, though, she wouldn’t be seeing any more fights in the basement of The Canteen.

I watched him up there shadowboxing, and my heart went out to him. He had no idea what his wife was made of. And he was so lonely in his work that he was willing to let a complete stranger off the hook if it meant being a part of something. I went to the cabinet behind the ring and got out two pairs of gloves and headgear and held them up. “You want to see what it feels like?”

He came over and leaned on the ropes. “And let you knock my block off? How do I explain that back at division?”

“We’ll take it easy. You’ll like it.”

He thought about it for a moment, then smiled and took off his jacket, tossing it over the corner as I stepped into the ring. I laced him up, but he waved off the headgear. “If I wear that, you’ll feel free to hit me.”

“It’s safer with it. Just in case.” I didn’t want to clock him accidentally, but he didn’t want to wear the gear. I tossed both protectors over the ropes. “Rule one: Keep your chin down. Tuck it into your lead shoulder, since you’re going to turn a little on an angle to me, give me less body to punch at. It’s natural to want to lift your head, but it’s the worst thing you can do. You got to protect both your throat and the button.” I touched the point of my chin with my glove. “And keep your hands up,” I told him, as we faced off. “Protect yourself and stay outside, you know what that means?”

“Keep back from you.”

“That’s right. Because you’re the bigger man here, you want some range. You want to keep me out from where I can work under your defenses, you understand?” He nodded. “And keep your eyes loose, like you’re trying not to look at me, but see my eyes and my chest and shoulders all at the same time.”

He nodded again, and we started circling each other, moving around the ring. He kept his hands up pretty tight to his face, but I could see him watching me between his gloves. There’s a lot you can learn from watching the fights, and he’d gotten it down pretty good, feinting away from me, keeping his head moving. I threw a couple of light jabs at him and he dodged them, returning punches when I was out of position and even connecting a couple of times, light jabs to my hairline. “That’s good,” I said, “you’ve got some ring sense.”

“You’re moving pretty slow.”

I started circling a little more aggressively, coming in when I sensed an opening, but he knew when to step out, break away. It was enjoyable. I’d sparred with Paschtenko, but that kid could knock me upstairs if he wanted to, and most of the time I spent in the ring with him, I just stayed away as much as I could. This was different, and in an odd way, it was a little intimate, like the beginning of a friendship. It was strange to have the man’s body in front of me, that body I had betrayed indirectly, at both a physical and emotional remove. This body so well known to Katherine. I suddenly felt grateful that he was not shirtless, that there was no more of the raw animal in front of me. I let us go a couple more minutes, connecting a few times, taking a semisolid punch or two to the kidneys from him. If he got into shape, he might have something, I thought.

I stepped back. “Well, officer, I should probably get back upstairs.” I’d lowered my gloves, but he was still moving toward me. I was completely open for the punch he threw, but I managed to slide away from it; he would have tagged me right on the chin. I batted his glove away. “Whoa,” I said. “There’s the bell.”

“Sorry,” he said, dropping his hands.

“Good instincts, though. Get yourself a trainer, you could put some tiger in that tank of yours.”

He picked his jacket off the turnbuckle, folded it over his arm. I stepped out and tossed the equipment back into the cabinet. “When’s the next bout?” he asked.

“Two weeks. You got a card?” He reached into his wallet and handed me one. He was sweating lightly. “So this is all going to stay on the QT?” I asked.

“Yeah, as long as you do what I say.”

“License, no ticket

sales.”

“Get rid of your records.”

“Right,” I said.

“And one more thing.”

I snapped the light off over the ring. “You were never here, right?”

“Yeah, that. And stay away from my wife.”

I had my back to him and I froze, waiting for the blow, but it never came. “What did you say?”

“You heard me, Terry. We’re giving it another try and I want you to keep your distance. I’ll let you know if it doesn’t work out between us.”

I turned slowly to face him. “Jesus Christ,” I said.

“I know.” He slipped an arm into his jacket. “You seem like a nice guy and I’ll be happy for her if we can’t get our act together. As long as you go semi-legal here, you should both be fine. But for now … you know.” He offered me his hand. After a second I took it.

“Look, I’m …”

“I’ll be seeing you, Terry.”

He released my hand. I felt it drop, dead, to my side. “See me where?”

“Here,” he said. “That Cooper girl really did swear a complaint. I’m glad she did. This is the coolest thing I’ve stumbled across in fifteen years.”

He went out the door without another word.

I turned off the rest of the lights and locked the doors. Upstairs the first wave was being seated in the bar. Gillian came over as soon as she saw me. The look on my face, I guess. “Jesus … was that guy from the commission?”

“No. He was a cop.”

“Oh fuck,” she said. “Is everything okay?”

“For now. But he warned me I could lose everything if I don’t clean up.”

She breathed out heavily. “Anything I can do?”

“Serve lunch,” I said. “What else is there to do?”

We did forty covers for lunch and another seventy-five at night. An average day in The Canteen. I looked him up online once I got home. He’d been an Ontario Golden Glove between the ages of sixteen and twenty-five. A heavyweight. He hadn’t won a single belt, but my guess is he didn’t want one bad enough.

I never heard from Katherine again, but after a few months, he started to show up at the fights. I said hello, but I let someone else serve him. Life is full of TKOs. You might think you’re still standing, but there’s the third man, waving his arms, and it’s all over.

For Steven Heighton and Michael Winter

BRIANNA SOUTH

BY RM VAUGHAN

Yorkville

BRI BLACKOUT! WHAT HAPPENED TO

HOLLYWOOD’S “BABY GIRL”?

—Toronto Sun, September 12, 2008

The following excerpt from Brianna South’s diary was obtained by the Sun from unnamed sources, three days after her shocking disappearance. South, the controversial seventeen-year-old star of last summer’s breakout comedy, All the Nice Girls, and the upcoming live adaptation of the ’80s cartoon series Pulsar Girl, set to close the Toronto International Film Festival on Friday, left her room at the Four Seasons Hotel in Yorkville on Wednesday evening for an unscheduled outing. South’s family have arrived from Fort Worth, Texas, and will make a statement later today. Police have released no further information.

September 4

Ugly. Okay, not the nicest thing to say, I know, but who said, “It’s not mean if it’s true”?

Probably somebody who came to Toronto and stayed a whole week in a room my grandmother would like, with thirty-six French TV stations and no hot towel rack and the worst warm walnut salad I’ve ever had, that’s who.

I’ve been outside exactly three times—from my hotel room to the service elevator to a town car to a raw food restaurant, then back, then to a TV station in an old factory that smelled like a hot dog cart, then back, then to a boring movie from Mongolia they showed in an opera theater.

Jayson said I should see it, or just be seen seeing it, or at least walk into the theater. Like I understood any of it anyway, like I understand Mongolian funeral rituals and polo. I hate polo. Then it was back to the car, back up the service elevator, back here. It’s so ugly. The view is of a museum that looks like another old factory, but with a bunch of bent aluminum siding sticking out of it, like a giant ugly metal rock. I think it’s supposed to be art. I hate my life.

Later

Nobody likes my film. I can tell, because they won’t shut up about it. If it was good, they’d be all calm and quiet.

I don’t even remember the Pulsar Girl cartoon, and I’m in the “target market” for the movie. Newsflash, idiots: Girls don’t go to comic book movies.

But you can’t tell them anything, they’re all fags. Only fags would make that movie. Everything is so funny to fags, stuff nobody else thinks is funny. Jayson said, “It’s already a camp classic” in the restaurant—he thought I wasn’t listening—and that is the fucking kiss of fucking death. You can’t make a cult movie. It just happens. Even I know that, but you can’t tell fags anything.

I hate Jayson. He leads me around like a dog. It’s his job to get me the best interviews and the best articles and so far all he’s done is drag me in front of people for show, not to talk. Nobody talks to me. They talk around me. I’m beginning to figure out that the whole point of this film festival is to just show up. I could be dead and they could drag my body from party to party and I’d still be the biggest news in town.

I mean, even Melanie Griffith got a newspaper cover, just for doing her own grocery shopping. She hasn’t made a movie in years, but the whole stupid city freaks out because she can pay for a braised chicken all by herself without a helper.

Okay, that was mean. I’m hanging around Jayson too much. I sound like a fag. I really, really need someone to talk to. I could be dead and nobody would notice.

September 5

He called again, just ten minutes ago. I’m too excited. I shouldn’t be this excited. I don’t know how he got my room number. Everything is supposed to be secret—where I go, where I stay, where I eat, where I shit (especially where I shit). But he found me. Hotels are cleaned by ex-cons, like Mom says, so it’s no surprise. What’s a few fifties up here—like, eleven dollars at home?

He is so smart, it scares me. He says he found forty-six minutes of Pulsar Girl on YouTube. He says it’s good, the flying looks real. I feel a little better.

[The remainder of the page is covered in drawings of hearts, vines, and what appears to be the same word, perhaps a name, repeated nineteen times. The word or name has been scratched out. Forensic textile experts hired by the Sun were unable to read the word.]

2:30 p.m.

I told Jayson to fuck off ten minutes ago. Fuck, that felt good. I should have done it before, like on Day One.

He wants me to go to this party in a science museum, a fundraiser for stem cell research. I told him I don’t believe in using unborn babies to cure varicose veins. So he said I didn’t have to pay to go, they only want me there for PR, so I wouldn’t really be supporting anything I didn’t believe in if I wasn’t paying. That’s Jayson logic.

I mean, I know I don’t act all Christian, but I do love Jesus and babies. And my parents would kill me. So Jayson says, “SharLynn Kashante Jefferson is going,” like that is supposed to make me all jealous or nervous or scared. SharLynn is okay. She’s nice and, okay, she is pretty, but come on—she’s on a stupid hospital show, with, like, four other black girls. And, I mean, really, only my father watches hospital shows.

So I told Jayson to fuck off. It just came out. Fuck. Off. Now he probably thinks I hate SharLynn, or that I’m racist. I don’t care, I don’t care, I don’t care. I mean, I don’t think they even get her show on TV up here.

He will be so proud of me when I tell him what I did. He says I have depths inside me, strengths and energies and powers I don’t even know about yet. He says I am all diamonds inside.

September 6

Worst breakfast press conference of my life.

I felt like this tree, this skinny, dry tree, like the kind that used to grow in the back

of our first house, behind the gravel pile. Garbage trees, skunk wood, Dad used to call them. You just cut that kind of tree down because it’s no use. It’s a weed with pretensions, Dad said. So you cut it down.

That’s the way they treated me. Cut, cut, cut, cut, cut. One guy from France asked me about Iraq, if Pulsar Girl could stop the war (!!!!). Like I’ve been to Iraq, or even Europe. So that’s all I could think to say: “Never been there.” They laughed, mean laughs. Jayson just sat there. He said his microphone wasn’t working. He fucking lies so much. Every word.

I lit all the foxglove-scented candles he sent and turned on Canadian MTV—which is, of course, in French, but at least the music is American—and I got in the bathtub and filled it really slow. He says foxglove is a medicine flower and the Irish call it Dead Man’s Thimbles. Doesn’t sound all that healthy to me, but he’s the expert.

We connect over things like that. I mean, he’s an expert in old things, in legends and stories, and I’m an expert in acting. The first time he wrote to me, I have to admit my Creepy Guy Radar went off a bit, because his handwriting was so girly. But I kept reading (because, okay, I was bored on the set), and he wrote that he thought All the Nice Girls was really a remake of the Story of Rachel and Leah, who are sisters in the Jewish part of the Bible. I looked it up.

I really am a lot like Leah, the “barren” woman, which I think means she was deaf. I mean, I’m not deaf, but I do sort of drift off a lot, and I am “tender-eyed” too, like the Bible calls Leah. I have a good heart, and I’m way, way too nice. And I’ve been overlooked all my life.

He’s coming.

[The remainder of the paragraph is illegible. Forensic textile experts hired by the Sun believe the page was scraped with a nail file or the blade of a sewing scissor.]

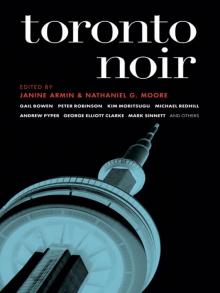

Toronto Noir

Toronto Noir