- Home

- Janine Armin

Toronto Noir Page 15

Toronto Noir Read online

Page 15

Now it’s 7:30 and Jayson was supposed to be here at 7 to pick me up. Another hospital party, for kids with bone cancer, or inside-out organs or bugs in their blood—something gross, it’s always something gross.

I will not hug the really messed-up ones. I told Jayson—no hugging and wipes, bring sterile wipes. He never listens.

This afternoon he was in here, going over my dresses for tonight, and I turned away to look out the window because A) I didn’t want to look at him because I hate him, and B) because there was this beautiful red bird on the window ledge. Bright red, and big, big as a cat.

Jayson said it was a Pope bird or a Thorny Cross bird, or another churchy name, like he knows anything, and after it flew away (actually, it really just sort of fell off the ledge, I hope it’s okay!!!), I caught Jayson fucking around with my phone, my private phone with all my addresses and numbers.

I said, “What are you doing?” and he clicked it shut like it was nothing to invade my privacy. He said he thought it was his phone, no bigs. But his phone is blue, and mine is tangerine. Jayson wonders why I don’t trust him.

I’ve decided I don’t care that I don’t know what he looks like.

Well, okay, I care a little, and I have an imagination, because I’m an actor—but if he’s really ugly or old I really don’t care.

I’ve met every good-looking man in the world in the last year and the big secret is all good-looking men are exactly the same. They’re like men’s dress-up shoes: They come in black or they come in brown, they have pointy ends or they have square ends, and that’s that for choices.

I’m so bored with “beauty.” I can look at any big actor now and I can tell you in ten seconds which trainer he uses, which diet he’s on, where he gets his facials, who fills his pecs with saline, or his dick. It’s like math, like algebra—squats plus tensor bar plus Nevada mud bath plus coffee enema three times a week equals one shower scene in your next movie. Do the same math five times and eat raw lamb for twelve days and you get a sex scene too.

I mean, if I can figure this out after two movies and one season on 7th Heaven, when I was like nine, why can’t the public figure it out? It’s amazing that people don’t just start shooting celebrities, just for fun, just to see how quickly the producers can grow a new one, like starfish legs.

I don’t think I’m unreplaceable. I don’t think I’m special, or like a part of history. No fucking way am I doing “art.”

Maybe college would be fun. I’d like to get drunk and throw up all over myself on a cute guy’s front lawn, like my friends back home do every weekend. Nobody worries that they’re “out of control.” It’s totally expected, totally acceptable behavior. I mean, Jayson even took the mini-bar key. “It looks better,” he said.

Better to who? The maid? Jayson is so controlling. And I pay him for it. That’s fucked.

He told me his name today.

Okay, it can’t be his real name, probably, but it’s still a name.

Azrael.

He said it was Jewish for, “He who makes the lasting peace.”

It’s beautiful, even if it is fake. Fake and beautiful are the same thing anyway.

Twenty-nine hours till he arrives. I’m excited, more than I should be. I should be excited about, like, one hundred other things in my life, but he’s the only mystery I have left. Once you’ve spent seventeen hours hanging from a green wire pretending to be scared of the end of a mop that’s supposed to be a giant lizard alien head, most of the surprises are gone out of life.

I mean, I could get pregnant, that would be new. That would be news too. Brianna and Azrael. What would the tabloids call us? Braz? Anra? Briel? Brianna and Azrael. Brianna and Azrael.

Please, God. Please, God, let him be cute. At least cute.

No, forget it. Sorry, God, scratch that. I am such a C-U-Next-Tuesday. I don’t care. Azrael can have three heads and a harelip on all three mouths. He’s a listener. My listener.

“He who makes the lasting peace.”

Ten minutes would be enough for me.

Fuck, Jayson’s here, at ten to 8:00. Nice and late. Off we go to pet the zombie kids. I wish I had some gloves—those long kind, up to the elbows. I could pretend it’s part of my outfit.

September 7

Needy—people are so needy.

If I had terminal cancer I would just want to be left alone.

I wouldn’t want balloons, or slides I couldn’t slide on, or an ice cream cake I couldn’t eat anyway—and especially no fucking thank you would I want fucking Mr. ET Canada Ben Mulroney signing my IV bag!!!

I mean, Jesus Christ!!! Why didn’t he just sign the kids’ foreheads so they can all be buried with his autograph? That guy is like an animatronic dinosaur at the Tar Pits—he moves his head, he opens his mouth, he moves his head in the other direction.

Best moment: Mulroney corners me while this girl who can’t stop moving her head is getting her face painted like Spider-Man (because he figures nobody can hear him over the girl going umma umma umma) and he asks me, all “real” and sweet and concerned, if I want to talk about Pulsar Girl and why I’m fighting with the director.

Please, why would I fight with a director after the movie is done? What’s the point?

I smell Jayson’s stale CK One all over this. Maybe that’s the new sell talk for the movie—Brianna’s tantrum. Somebody has to be blamed, and it’s never the director because here’s another big secret: Directors are pure profit. You can work a director till he’s like ninety-five, as long as he can point at the actors and mumble.

The sad part is, the kids were really excited to see me. I don’t get it. Maybe one of them, maybe two, has ever even seen me in anything. But Somebody Special was there, and that’s all that mattered.

I kind of think that if I only had a few weeks to live, I would consider myself the most Special person on earth, as a survival strategy. I would let all my animal instincts take over, become totally selfish and full of self-love, even self-worship. I would save every breath for me.

September 8

Azrael sent me the most beautiful plant. I wonder if I can take it back on the plane?

It’s an orchid, I think. There’s no real roots, just a ball of hard wood underneath this cloud of green spongy stuff that looks like a pot scrubber. The flower is navy-blue, or purple, I can’t tell. It’s huge, the size of two grapefruits, and it smells like dish soap, but salty. That part I’m not liking so much.

His note says the flower represents “purity risen from offal” and that the flower has “cleansing powers.” That explains the smell.

I asked Jayson what “offal” meant, but he just went all faggy on me and waved his hands around like I just farted. He says the flower looks like something you put on a coffin. He would know.

September 9

Another fight with Jayson.

He wants me to do a breakfast television show tomorrow, at 6 a.m. It’s a total waste. People who watch television at 6 a.m. don’t go to the movies, because either they are senile and stuck in a home, or because they have to go to bed at 5 p.m. to get up for 5 a.m.

It’s a total waste of time. I mean, maybe I’d do it for Good Morning America or Today, but Canadian breakfast television? Why don’t we just set up a webcam in my room and beam pictures of me to Yakistan, or wherever? It would amount to the same at the box office.

So, I said no. I am allowed to say no.

Jayson freaked, really freaked. He screamed crazy stuff at me like, “I know more about you than you know,” and, “I’m the reason you’re here.” Over and over. I walked into the bathroom and shut the door. So he stood there, right outside the bathroom door, close enough to hear me piss, and I think he was crying!!!

I came out after, like, twenty minutes (because I was bored and that bathroom is beyond ugly), and he was standing by the window, perfectly still. Calm as a sunflower, like my grandmother used to say.

“What have you got to wear if it rains?” he says. What a psycho.<

br />

I sent him to get me some new makeup, which I do not need, to get rid of him. I think I’ll “forget” to pay him back.

I hope you can get Google Maps in Canada. I have to find out where Leslie Spit is (I know, eewww, gross name).

Azrael says it’s the most private place in Toronto—a beach with trails and tall grass and flowers and, I guess, the ocean.

That tells me two things: One, he is from here, which is too bad because I hate long-distance relationships, and two, he is not interested in publicity, he doesn’t want to be Mr. South.

He just wants to meet me, like a person, the way people are supposed to meet—without some Jayson or whoever in the middle, some fixer or arranger or scout or manager or protector.

I am so bored with being protected. It’s not natural.

I mean, if I can’t figure out who my friends are on my own, how am I going to make it to, like, twenty-five?

I’ll get eaten alive.

MIDNIGHT SHIFT

BY RAYWAT DEONANDAN

University of Toronto

Over here,” Meera said, taking Yanni by the hand and dragging him down a freshly mopped corridor.

It stank of ammonia, an antiseptic nasal assault that held a warped erotic appeal for some among the stethoscope and lab coat set. Meera drew Yanni’s mouth to hers and tasted his youth, inhaling his masculine scents and flavors.

“Slow down,” Yanni whispered. “And be quiet. Someone will hear!”

“Wimp,” Meera chastized, running her dark hands under Yanni’s loosened shirt. “There are only two nurses on this floor, and they’re both at the station.” Yanni still hesitated. “Besides,” Meera continued, “maybe you want to get caught?” She grinned in her devilish way and pinched his nipple, pushing Yanni against the sterile white wall.

He was yielding to her touch, soft clay beneath her willful hands. Meera pressed him against the sign that read, 2nd Floor, Rheumatology. The irony was not lost on her, as they strived to express an act of guileless youth in a place of broken agedness. The odors of imposed sterility, the colors of bureaucratic lifelessness and joyless dull lights—these were tokens of a philosophy that pushed aside the ardor of youth, the mystic charms of sex, and dirty, musical physicality. It was as if she and Yanni were consecrating the lifeless drywall with their hot, staccato breaths, all the time mildly aware of the clicking heels of the midnight nursing shift a hallway away, and of the almost imperceptible groans of the elderly patients swimming in their beds, wracked by dreams impossible for naïve, young medical residents to comprehend.

They clutched each other in that particularly desperate way, with each muscle seemingly both shocked and delighted that it had been recruited to such a pleasant purpose, and melted into the slow rhythm of human intimacy. The barren hospital corridor seemed less foreboding now that their eyes became accustomed to the darkness. At the end of the hall, a small window was open, letting in dull sounds from University Avenue below: a rushing stream of honking taxis, whooshing motorcycles, traffic lights hooting and chirping for the blind, and the chatter of the occasional passersby.

“Come on,” Yanni said, spinning from the wall and dragging Meera by her stethoscope. He pulled her into one of the empty patient rooms and onto a bed. The tightly tucked hospital sheets were a cliché, one that made them both chuckle as they gave up trying to get under them. Then they heard a noise.

“Who’s there?” It was a man’s voice, weak and desperate.

Yanni sprung to his feet, letting his open shirt fall back into place. “I’m Dr. Rostoff. This is Dr. Rai. Who are you?” Meera clicked on the room light, revealing an elderly man in the room’s secondary bed. “This room is supposed to be empty.”

“Manoj Persaud,” the man said, looking pleadingly at Meera, perhaps finding solace in a face as brown as his own. Yanni snatched the man’s chart, flipping through the long paper sheets with guilty annoyance.

Yanni frowned. “Meera, he’s supposed to be in the Latner Centre.” He whispered: “Palliative care.”

“I know I dyin’,” Manoj Persaud said weakly in a slight Caribbean accent. “Na need fo’ whisper.” He pulled himself to a sitting position on the bed, revealing striped pajamas and furry pink slippers with bunny ears. Meera smiled at the sight. “One a dem volunteer give dem to me,” Persaud said, gesturing to the slippers. “When I dead, you can tek ’em.”

Meera sat next to the strange man and started with the usual doctor routine: the pulse check, the penlight in the pupils, an examination of the mouth and tongue. Persaud pushed her away. “What you doin’, child?” He coughed blackishly. “I said I dyin’. You go find somethin’ new fo’ kill me faster?”

Yanni dropped the file onto the bed and sighed. “Mr. Persaud, you are eighty-eight years old and suffering from several very serious medical conditions. I don’t know how you got to this floor or this room, but we have to get you back to the Latner Centre right away. They can take care of you better. We just don’t have the facilities …”

“Boy,” Persaud coughed, “I come down here because he comin’ for me. He go get me sometime soon, but he cyaan do it now. Na now. He got fo’ wait till me ready. I got fo’ hide, just fo’ tonight. Just until me can tell somebody m’story.”

“Who?” Meera implored, stroking the old man’s face and feeling cold, wet fatigue. “Who’s coming for you?”

Persaud’s eyes widened and his jaw dropped. He leaned forward and beckoned her closer. The room seemed to darken then, with the hum of the old ceiling fan fading into the ether, and a taste of slightly stale honey upon the air. “Yahhhm,” Persaud said, in all solemnity. “Yahhhm come fo’ me.”

Yanni frowned, but Meera motioned him back. “Yama,” she explained. “The Hindu god of death.”

“Yes, Mr. Persaud,” Yanni said. “I’m sorry, but death is coming. For all of us. For you sooner, though. I’m sorry. Which is why it’s important—”

“Shut up, boy,” Persaud said sharply to Yanni, then turned to Meera, cupping her heart-shaped face in his spotted hands. “You undahstand, right? Yahhhm come fo’ me, fo’ tek m’soul. And dat’s all right, child. Dat’s all right. Is okay. But na now! Na right now! Not before me can tell you why Yahhhm come fo’ me personally.”

Yanni pushed his hand through his thick blond hair and sighed again. Typically, rheumatology rotation didn’t involve psychiatric consults, but the midnight shift was famous for its many exceptions. And psychiatric issues were certainly not unknown to downtown Toronto hospitals. He reached for the phone by the bed, but Persaud intercepted with his skeletal hand.

“Boy. Please listen.” Persaud’s eyes were those of a doomed beast, pleading upward from the abattoir floor. “Yahhhm is comin’ here. Tonight. Right now.” His eyes slowly drifted to the hallway, to the open window at the end. Instantly, from the street below, there was a loud smashing noise, followed immediately by the sickly sound of bending metal and the unmistakable screams of humans in distress.

Yanni and Meera raced to the window. From the other end of the hallway, the shift nurses were also running to windows, so loud was the noise. Down below, like a report from the evening news of any unnamed metropolitan center, a scene of traffic horror unfolded. Two delivery trucks had collided and were blocking traffic on all six lanes of University Avenue, sprawling across the pedestrian median and had even knocked down one of the ghastly statues that usually stood watch. One truck was on fire, and police and fire engines were miraculously already on the scene. No casualties could be seen through the press of onlookers, who continued to stream in from nearby Queen Street, likely drawn by the sounds of disaster; but no doubt the emergency room below would soon be pressed into duty. It was an excellent ER, Meera knew; one of the best in the country. Still, a part of her wondered if she should rush down to help.

Persaud coughed loudly and beckoned them to the bed. Meera came back to his side. “Yahhhm,” he said, as if in explanation. “Death comin’. Na got too much time. Got fo’ tell you m’stor

y first!”

“Look at all the people down there!” Yanni called from the window, amazed by the flow of late-night disaster voyeurs descending on this otherwise unpopular street. “I know it’s a horrible thing, and I hope everyone’s all right, but what a show it must be on the ground!”

Persaud stroked Meera’s face then fondled her stethoscope. “You so young to be among we so old. And dis,” he indicated the end of the stethoscope, “dis does give you comfort? You med’cine cyaan stop Yahhhm when Yahhhm want fo’ come.” He grinned an awful toothless grin that slitted his yellowing eyes and widened his gaping nostrils. But there was nonetheless something attractive and familiar about him. “How old you be, child?”

Meera said nothing.

“Is okay,” Persaud said. “No need fo’ answer. You daddy dead, right?” She nodded, almost zombie-like in her silence. “Is okay,” he soothed. “We all got fo’ dead. Is okay.” Meera’s face hardened. Whatever slight spell the strange old man had cast on her was now fading, chased off by the invocation of her father’s sacred memory.

“Dr. Rostoff is right,” Meera said. “We have to get you back to your room. Then we’d better go to Emergency to see if we’re needed.”

Persaud’s lips tightened and he studied her carefully. He turned to Yanni, who was still bewitched by the scene of carnage on the street. “You, boy! Tell me you see Yahhhm.”

“What?” Yanni, annoyed, waved Persaud away. He kept looking through the throngs on the street. To a man, each was enthralled with the heroic acts of firefighters hosing down flaming trucks and pulling bodies from crushed vehicles. But there was one …

Persaud called to Yanni. “You see him, na? Tell me!”

Yanni was silent. But he kept his eye on this one special man on the street, this one man who was not watching the carnage. Instead, he was looking up, directly at the window from which Yanni now peered.

“Describe he!” Persaud ordered. But Yanni remained silent. The watcher continued to stand apart from the crowd, his hands in his jacket pockets, locking eyes with Yanni. Yanni’s fingers yellowed as they gripped the windowsill more tightly than was comfortable, but he snorted dismissively at the watcher.

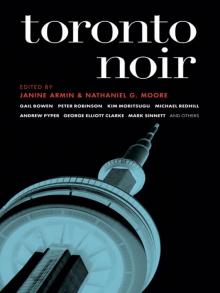

Toronto Noir

Toronto Noir