- Home

- Janine Armin

Toronto Noir Page 16

Toronto Noir Read online

Page 16

Meera gazed over at her friend and colleague, and was at a loss. She was torn in many directions, ripped apart like one of the vehicles in the street. Competing responsibilities and desires jockeyed for priority. Yet the balance of her focus remained on the strange old man in the bed next to her.

“You is Indian,” Persaud said. “You go undahstand. Dat is why you been sent fo’ hear m’story.”

Meera shook her head slowly. “Mr. Persaud …” She paused, knowing that further appeals to him to return to Palliative Care would be met with stolid refusal. And with the emergency outside, it was unlikely she would find sufficient help to move him against his will; not without sedating him.

She fell into his gaze, so sad yet intense. His yellow fishlike eyes bent into that sad configuration, and the spotted skin on the sides of his face drooped in its losing struggle against time and gravity. He looked so familiar, so sadly familiar. “I’m not Indian,” she said. “Well, I’m of Indian descent; but I was born in Kenya and grew up here in Toronto …”

“Doesn’t mattah,” Persaud said, shaking his head forcefully. “You is Indian. Like me. I was born in Guyana. Never been to India.” His accent seemed to be thickening as the evening progressed. But Meera had no trouble following. His gravitas commanded complete focus and understanding. “Never been to India,” he said again. “Don’t know m’caste or m’daddy’s caste. But I is a pandit just the same. One priest of God!”

Meera reflected, was tempted to smile. Her own father, whom this man so wished to resemble, had hated religion. He had refused to raise his children with religion, had thrown his wife’s idols from the home, and had famously quipped, “When things go well, we thank the gods. But when things go to hell, we blame everybody but the gods! What bullshit is this?” Yet in the end, even he had asked for a priest.

“You were a pandit in Guyana?” she asked him.

“Yes,” Persaud said. His face darkened and his eyes deepened. The sounds of the street seemed to retreat then, isolating Meera alone with the old man, cushioned from Yanni, the window, and the rest of the world. “I is a pandit now, and I was a pandit then.” He paused and stared at her meaningfully. “I was a pandit of Kali.” He spat the last word.

Again Meera smiled. “I didn’t know Kali was so popular outside India.”

“Kali be another face of the same God,” Persaud said, screwing up his own wizened face in mock dismissal of her seeming ignorance. “Goddess of blood, she. Goddess of glorious bittah red wine that pump in we veins. She scare the white people, na. But we know: She be a mama just like any lady. We respect Mama. We respect Daddy. And when you is a slave or servant in the cane fields of Guyana—back when the white man tek all you history, all you possessions, all you beliefs, and give you Jesus Christ instead—when you is a slave or a servant, you need cling to you mama and you daddy with greater force!” His gaze intensified, as did his hold on Meera’s hand. “Because dat is all you got, in the end. Dat is all you got.”

It was then that Meera noticed Yanni was being uncharacteristically quiet. She looked to him and saw only his back, with his untucked plaid shirt whipping in the wind from the window. “Yanni,” she asked, “are you all right?”

“He’s just staring up at me,” Yanni replied. He continued to look down into the mêlée below, red and yellow flashing sirens reflecting off his expressionless face.

“Yahhhm,” Persaud intoned. “Tell dis old man, please, boy. How the god of death look? He tall? He old or he young? How black is he face? When he come, I not go see he. He go tek m’soul and I not go see he face.”

Yanni replied without intonation, only fact. “He’s about twenty-one, five foot eight, but quite heavyset, wearing a white-and-blue University of Toronto jacket. And he’s blond … and white.” Persaud jerked at the last. “Maybe he’s just catatonic. Or in shock. All he does is stare up at me; at this window. Maybe he needs a doctor.”

Meera squeezed Persaud’s hand, then stood up. “Yanni,” she said, “it’s time we went to work. Let’s send for a wheelchair to take Mr. Persaud back to Palliative, then you and I had better report to Emergency. You think?”

Yanni detached himself from the window and scratched his head. “Sure, M. Let’s go.”

“Wait!” Persaud bellowed. “Listen! All me need is ten minute. Just listen a m’story fo’ ten minute, then you can do what the hell you want fo’ do. Yahhhm go come before ten minute. Just listen a m’story, na. I got fo’ tell somebody before me dead, or Kali go cuss m’soul.” He stared at the two of them for a good long couple of heartbeats. “You want she fo’ cuss m’soul? No? Good. Come listen, na.”

Yanni made an odd dismissive noise and returned to his post by the window, voyeuristically surveying the crowd. Sheepishly, Meera moved back to Persaud’s side, an imploring look in her eyes. “Okay,” she said. “Tell me. But then we have to take you back to your own room.”

And Manoj Persaud launched into his tale …

It was years before Guyana had obtained its political independence from Britain. The decades that had passed of slavery for the blacks, of near genocide for the natives, and of indentured service for the Indians had bred a thirst for release from the chains of colonial rule. With each layer of Europeanness painted atop this weather-beaten Asian and African tapestry came a strengthening of its foreign matte, a calling for connections to lives and philosophies left centuries and fathoms away. African animism, sporadic puddles of voodoo, the naturalistic magics of the scattered native tribes, and the myriad faiths smuggled from India all found fertile soil in this wet chasm of discontent. Amongst the Indian immigrants, the cult of Kali was revived and flourished.

In the telling of the tale, Persaud gurgled and his words took on a distant tenor. “Goddess Kali,” he whispered. “Omnipotent power absolute. She be the origin of cosmos and spirit. Deity of time, eternity and source of all energies. Kali bless us and we triumph over evil, destroy rogues and knaves, expel inauspicious souls, and repel demons.” He focused on Meera again, slowly intoning, “She be knowledge. She be bliss.”

Meera felt the dying man’s pulse again, worried for his stress. She opened her mouth to speak, but Persaud covered it with his quivering hand. “Let me finish, na. You got fo’ undahstand. The white man, he afeared o’ Kali. He think she be demonic, wit’ blood and scariness. But dat is fo’ he. Kali is we mama. She be the female face of God, the angry mama who does protect she pickney, she children. We is she children. It is—what you say?—a metaphor. We weak before the white man, so we need one strong image of we mama fo’ protection. You see?”

Meera nodded. And Persaud continued his narration …

Manoj Persaud had been a priest at the temple of Kali, where scores of devotees came weekly, sometimes daily, to offer obeisance to the mother goddess. In exchange, they received stable employment, healthy children, enough food to last the month, or whatever else it was they prayed for. It was Persaud who interpreted the omens and prodigies, who interceded between mortals and goddess. It was Persaud who interpreted the lost ways of obscure India to the subcontinent’s forgotten and wretched Caribbean progency.

But tensions were mounting as demands for political independence grew louder on the streets, in the newspapers, the rum shops, and even within the temples. “And one day,” Persaud said, “dem came fo’ talk wit’ me.” Six men they were, regular devotees of Kali, some even Persaud’s relatives. They abased themselves before the priest and asked for a special puja, a divine way or ceremony, for Kali to guarantee and accelerate Guyana’s impending independence.

“I tell dem fo’ pray and fo’ make sacrifice to Kali, like dem always do, wit’ coins, food, and fasting,” Persaud said, a sense of both sadness and horror growing behind his eyes. “But dem say dem want something extra. Something more. Fo’ Kali. Fo’ big big magic.”

The younger Persaud had watched his devotees with growing unease, as the full extent of their petition came to be understood. For a boon of this magnitude, one affecting a who

le nation of people, the old ways would have required a human sacrifice. But modern times employed modern methods, with pumpkins standing in for human heads; or the use of human effigies constructed of flour and mud, slashed with razor-sharp machetes. Persaud presented these tamer options to his petitioners.

“But dem know the magic,” he said with growing weariness. “Dem know the sacrifice, how the sacrifice must be aware. It must know it own fate and not be acting to stop the cutlass.” Only then would the magic work, when the ultimate unseemly price had been paid. Only then would Kali grant them their wish.

Meera grew pale with the unfolding of the tale. Like a journey taken on a cloudy morning, its horrifying destination was rapidly becoming clearer as more steps were taken. Persaud’s face was pleading, almost desperate with apology. “No,” he said. “I not want fo’ do dat! I tell dem. Dis pandit does not hold wit’ dem old ways!”

But he had to tell them something. If he just sent them away, who knew what atrocity they would enact? Perhaps they would kidnap some poor fool and murder him sloppily in their own homemade Kali puja, accomplishing nothing except creating misery for all involved—and offending God in every way possible.

“So I tell dem,” Persaud said. “I tell dem: It must be a white child. Dem must kill one white child.” He sat back against the wall, grinding his gums, waiting for Meera to react. But there was only silence.

Meera regarded him with a strange detachment, struggling to balance horror with pity and disgust. She felt herself slide backwards, her hands near her face.

Persaud leaned forward again. “Undahstand! You got fo’ undahstand! Where dem stupid boys go find one white child? We never see no white pickney. Only white man wit’ he gun, he whip, and he stick. Where dem skinny brown village boys go get one white child? I been tryin’ fo’ save dem, see? I been tryin’ fo’ prevent dem doin’ some damn stupidness!”

Persaud’s eyes exploded into tears. They rushed like torrents down his cheeks and into the sides of his huffing mouth. His breathing was shallow and forced, wheezing at times between bouts of fitful, pathetic wailing.

“I been tryin’ fo’ mek dem task impossible,” he whispered into the tissues Meera was using to wipe his face.

“But it wasn’t impossible,” Meera asked cautiously. “Was it?”

At that, Persaud reached into the front pocket of his pajama pants and pulled out a crumpled, yellowed piece of newsprint. Meera took it and unfolded it. On the top it read, Stabroek News, Georgetown, Guyana. The date was 1961. It was a story about the disappearance of the baby daughter of the overseer of a sugar cane plantation in rural Guyana. Her name was Helen and her surname was seemingly Dutch. There was no photo, but Meera assumed the girl was white.

“My God,” she said aloud. “They found one.” Persaud nodded and sobbed. “But how can you be sure they killed her? Or that they were the ones who killed her?”

Persaud laid back against the headboard of the bed, spent. His face glistened with tears and sweat and his head now resembled a desiccated brown skull. He seemed to be aging before Meera’s very eyes. Unexpectedly, he smiled in that dejected but resigned way that the elderly sometimes do. “I know,” he said, “because dem bring me she body. Dem wanted fo’ know if it been done right, according to the old ways.” He breathed sporadically now. “And I told dem yes. Yes, it been done good, according to dem damn old ways. Yes.”

Meera stared at the pathetic old man, suddenly aware that she was watching death creep over him, consume him cell by cell. It was an oddly emotionless observation, one that shamed her and pushed her back into her professional demeanor. Only then did she notice that Yanni was standing behind her, his hand on her shoulder. “You heard?” she asked him.

“Yes,” Yanni said. “It’s a city of immigrants, you know. Everyone’s got secrets and stories from some faraway place. We’re supposed to start fresh when we get here, no? Let’s take him back now, okay?”

But Persaud was not done yet. “Boy,” he said weakly to Yanni, “Yahhhm comin’ now. Go and see.”

Yanni slitted his eyes in annoyance, but returned to the window nonetheless. He rushed back to report to Meera: “It’s true. The fellow who was watching me is gone. I think he might have come into the hospital!”

Persaud’s face contorted then. With surprising strength, he locked his hand onto Meera’s arm, hurting her slightly. “Yahhhm comin’!” he gasped. Meera could sense the otherworldly terror that possessed Persaud, but could do nothing for him. She tore his grip away and began sifting through the room’s supplies, searching for a sedative.

From the empty hallway came the unmistakable sound of approaching footsteps. These were not the steps of the nurses, who wore sneakers or delicate high heels, but of a large man in boots. Meera’s eyes met Yanni’s and the young man leapt to his feet and to the door, just in time to intercept a blond youth in a blue-and-white University of Toronto jacket. “You!” Yanni barked at him. “Visiting hours are over. You’re not supposed to be here.”

“Sorry,” said the young man, looking about the room sheepishly. “I’m with the student paper. I saw the light coming from the window and thought it would be a good place to get an aerial photo of the accident.” He pulled a camera from his jacket pocket and showed them.

“You’ll have to leave. Sorry.” Yanni pushed him back into the hallway and toward the exit. “See?” Yanni called back to Persaud. “Not the bloody god of death!”

But, of course, Persaud had already expired. His lifeless body lay sprawled atop the bed, like a grotesque skeletal clown bedecked in striped pajamas and pink slippers. His final expression was not that of an old man placidly accepting his final rest, nor that of a holy man content to meet his god. Rather, it was a pose of profound terror and worry, with crevices of skin radiating around his open mouth and his gaping yellowish eyes. Thankfully, Meera was not reminded of her father. He had had the good grace to slip from mortality with silent dignity, his worldly tasks completed, and with no important words left unsaid. But, she judged, not so for Manoj Persaud.

“I thought telling his story was supposed to bring him peace,” Yanni said.

“I don’t think he told us the whole story,” Meera explained. “He said they brought the girl’s body to him. But he didn’t tell us that she was still alive at the time.”

Yanni slipped his hand into hers. Meera stretched up and kissed him on the cheek.

“Hey,” she whispered. “Midnight shift is over.”

CAN’T BUY ME LOVE

BY CHRISTINE MURRAY

Union Station

Union station. 6 o’clock. Commuter-throng in the basement concourse. Head-numbing fluorescent lights, the terminal as garish as a 1950s office space. I breathe in the odorific confluence of fast food and rubbersoled shoes and scan the room for a free bucket seat, preferably one with a view of the overhead screen. Train’s not up there yet, so I’ve plenty of time.

I locate a seat between two average-looking drones. The lady to my right ruffles her newspaper back and forth like a perturbed swan beating its wings. She gives me a peripheral going-over and crosses her legs purposefully, cinching her ankles together. To my left, a mid-forties businessman reads from a men’s magazine with a semi-naked brunette on the cover. I recognize her—young actress, former child star. She’s on her knees, legs apart, back arched, blouse open above the navel.

There’s something attractive about Union’s retro décor. Its generic quality makes it easy to ignore. You can see the people for the trees, so to speak. Not like new terminals, where you can’t see the people for the gleam off all that stainless steel. Different story here, from the dude engrossed in “Real-Life Sex Injuries 101”; to the lady now methodically folding her newspaper into accordion-style strips; to the platinum blonde with long silver nails standing at the bay of pay phones dead ahead. She’s wearing a neon-green mini-dress, rollerblades over her shoulder. Cradled by her neck, the phone seems too large for her childlike head, the black receiver as oversize

d as a clown’s shoe—a clown’s phone.

I’m not a perv, but let’s face it, I’ve nothing better to do than to watch neon roller girl over there. I’ve already visited the magazine store, bought a cinnamon bun. I have a coffee in my hand that’s so Ibiza-hot I could spill it on my crotch and sue for damages. It was sunny on the walk from the office, but the smell of autumn left my nose lightly frosted. I’d bought the coffee to keep my hands warm. I hadn’t decided whether to drink it or not, but now, out of boredom, I flip the sip-lid, snap it into place.

The talk went well today—better than expected. “We like what you’re up to, Chris,” Darrin had said. “Want the whole team to follow your lead. Show them how you’re doing it. Get them to reinvent the fucking wheel.”

The wheel was ad copy. I’d come up with a new approach I liked to call ad absurdum. Only, I didn’t come up with it; loads of writers were doing it already:

“Say a product is new and improved,” I’d explained today, clicking through slides. “So, you write New and improved on the packaging, right? Trouble is, there is nothing more dusty and hum-drummy than writing New on a new product. What to do? … What you need is to make up a new word. Trick is, you’ve got to make it sound like other words, using known prefixes and suffixes, so that your audience understands it right off the bat. No sense speaking a language they don’t understand, see? It can be as easy as adding -tastic to the end of word, as in Tastetastic! Or as tricky as launching a frying pan around Halloween with the words, Terrifry your food!

“Think about it,” I’d concluded, leaning over them. “Edutainment might be a word in the dictionary now, but it didn’t used to be. We need to harness the power of hybrid words. If we trademark them, we could actually own our own language—and just think of how advert-ageous that would be!”

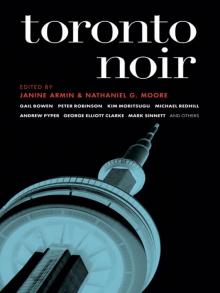

Toronto Noir

Toronto Noir