- Home

- Janine Armin

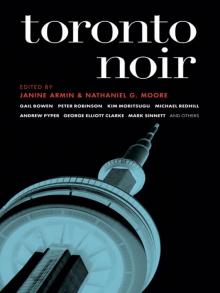

Toronto Noir Page 21

Toronto Noir Read online

Page 21

“Listen,” Cynthia said into the black slots in the mouth-piece. The telephone was the most efficient way of both delaying and prolonging the devine glut of mayonnaise crucial to the supposed low-fat wrap. “I know you can help me. I want you to wave your magic wand and find me a driver by Friday.”

The coworker gingerly deposited her lunch things in the garbage and reached for her Day-Timer. Cynthia turned away from her, leaned back in the swivel chair, propped a squaretoed black shoe dangerously close to the sandwich, and eyed it with contempt.

“Friday,” Cynthia said again, louder, “I know it’s close, but you’d be such a dear … I would definitely owe you lunch.”

She hung up.

“Idiot.” Cynthia ground the word between her teeth and the woman looked up with surprise. “He wouldn’t lift his finger; take his wife’s pulse if she were dying.” Cynthia laughed loudly, the chords of it straining through the office wall out into the village of cubicles. She shook her head in feigned affection. “He’s going to do me this favor; he doesn’t even know he’s getting the boot. You didn’t know? Well, it’s not like I’m asking for anything out of the ordinary, nothing that isn’t in his job description. You have to cut the dead wood. Really, nice enough guy, that Jackson, but rocks for brains. Andy came in here the one night, laid it all on me, told me about Jackson at the last conference. He did this performance you wouldn’t believe—you just don’t talk out of line like that, ever. I can’t believe I didn’t tell you this. Andy came in one night, said, ‘We’ve got to lose senior staff. If not Jackson, then who? I hate to do it to him, I just need one reason to keep him on, something solid, help me think of it, one thing I can take to the board.’” She held out her arms emptily.

The smell of the sandwich crept into Cynthia’s nostrils. She grabbed it off the desk, took six small bites, the medicinal fish taste oozing through her wisdoms. She chewed until the pita slid down her palate without struggle.

“But that’s business, it’s all balance.” She stared down at the nub of sandwich. “In the long run it’s better for the company. Jackson will do me this last favor and then we’ll be even.”

A few rings of green onion lay on the wax paper, an insideout company logo showing through from the other side. Out of the bottom, a thin milky trail leaked. Cynthia balled the half-sandwich inside the paper and let it fall into the wastepaper basket. Her coworker offered her a piece of chewing gum, the silver foil crackling. She chewed it hard and fast, pushed it with her tongue against the roof of her mouth where it would stick without looking unprofessional. It deposited a burning twiggy taste of mint.

Bonnie Brown-Switzel stood outside the pharmacy beside battered newspaper boxes that had been ransacked, neon flyers for burlesque shows and ESL tutors rubbing paper shoulders. She fumbled through the white plastic bag, searching for her purchase. Her fingers clamped around the tube and she experienced a youthful thrill. She rummaged in her black leather shoulder bag for her compact. The oval of her mouth was powdered, her lips slightly chapped from walking all day.

This was her prize. The classic vixen’s tool. The tip of its perfect red tongue met her bottom lip where she let it linger before climbing up to accentuate the peaks. It was, if not the same color that the woman on the actor’s street had worn, very similar. Bonnie usually steered clear of bold colors. She was feeling reckless. She peered into the handheld mirror, very pleased.

“Can you lend me thirty-one cents?”

She hadn’t heard him. He was right at her elbow. When she looked up, his eyes burned into her.

“Just thirty-one cents. All I need is thirty—”

It was growing dark already. Bonnie shook her head and bolted a few feet, stopped by a youth on his bicycle.

“Yo, watch it,” he called, swerving, the bike dropping down from the sidewalk to the curb into oncoming traffic, spraying thick black slush.

When she looked down she saw that she had crushed the head of the lipstick into the tube, damaging its shape. It was not broken, but its newness was gone. She pulled a tissue from her purse and wiped the lid, pushed the compact and the recapped tube into the depths of a side pocket in the purse as she walked, even though she knew they would lose themselves between empty gum packages, business cards, and store circulars.

“Hooor!” the homeless man called after her. “Bitch!” A wave of heat knocked against her forehead, and she sped up a few steps. When she glanced back over her shoulder, she saw he was already engaged with someone else, a thin man in dirty flannel and a pair of bedroom slippers. “I’m not a man!” her original fellow was yelling, his head turning between the new arrival and a couple of passersby. “I’m not a man!”

Bonnie ducked into the doorway of a bar she had passed many times before. Its entrance was littered with weekly newspapers. She would pop in and catch her breath, flip through a paper in the foyer, pretend to look for a movie time or an address, and then duck out again when the street had quieted. Between the two doors it was light, she could hear a familiar swell of music, the tinkling of glasses from inside, see the white-shirted man sliding them into the rack above the counter carefully, as if he were dabbing paint on a canvas. His eyes penetrated the door and connected with Bonnie standing there. Before she could pick up the club mag, she was grasping the handle and she was inside the second door.

Volker Gruber watched nothing with interest. His movements were slow and precise like one who is waiting, saving all his energy for something greater. Noon to 8, he told himself, another two hours, another thirteen dollars. Ten would pay his way in. Five for his first drink. Another two hours and he was already in debt to his plans.

He stared absently, trying to make sense of his losses, as an older woman stood between the doors of the establishment, disoriented, bobbing back and forth to some kind of internal flutter, apparently deciding whether or not to come in. The sound system overhead bleated something utterly offensive, the same line quadruple-repeat. A chorus in another language was no more interesting than in one’s own. Without focusing, Volker could feel his eyes burn dark with annoyance.

He could have no idea that this would be his last night in Canada, no idea that 6,197 kilometers away, Herr Gruber had clutched a hand to his fatal heart. Volker stilled, unsure if he should greet the woman or go back to the kitchen. In moments of indecision, his head filled with great handclaps of static.

The woman maneuvered her way past empty tables up to the bar and perched pertly on the stool. She had thirtyish thighs and moved off-cadence, like a skeptical cat. Had he seen her before? She seemed like so many of their customers—styled exactly so, but still the uncertain type, with thick dark hair. She liked him, he could already tell. The dark ones always did. He smiled at her. The bartender, Vincent, was in the back. Volker placed his hands on the counter, elbows out, like he owned the place. People were so gullible. She would be gullible too.

The woman licked her lips, the color on them reducing ever so slightly. She gazed up at a chalkboard above Volker’s head. He gave her the eyes. She looked at him, glanced up, looked at him again.

“I’ll have a … a … maybe a …”

He reached behind himself and fumbled for a bottle. He hated to waste a rock glass with two hours to go. He always ran out of the short rock glasses first. A bottle of red wine raised, Merlot. “Mer-lot,” Volker stated, letting the words fill his mouth, thick and red. “Mer-lot?” He lifted his eyebrows. Their eyes met. She nodded. “Mer-lot.” The long-stemmed base plinked against the counter.

She fumbled in her purse. How much? Neither of them knew. She pulled out seven dollars and set it on the bar. He looked at the money. She added another dollar. He set the sky-blue five atop the cash register for Vincent to ring in. Three made their way into Volker’s pocket, where they jangled together, crisp and sweet. He grinned at the woman, nodded, and made his way back to the kitchen, his hips already stepping to the rhythm to come. He could feel her admiring eyes beating a soft steady path between his shoulder blade

s on down.

Cynthia Staines put her turn signal on and edged over toward the snow-gray Jameson exit. She checked her blind spot at the last second, just in time to avoid the front end of a hurtling red Malibu. The old muscle car hit the gas and the horn simultaneously, surging dangerously near as it burst ahead of her with a penile display of pride.

Cynthia swore loudly. She edged over tentatively and then sped up to ride his bumper. He slowed, and she slammed her foot on her brake. He was on and off the brake lights like he was playing the drums. A vicious urge to smash right into the inane license plate—BRADCAR—forced Cynthia to lay on the horn until the guy sped off down Lakeshore Drive where the exit merged with the street.

Cynthia turned, cruised a few blocks, cursing, until the need to pull over stopped her. She was shaking. She snatched a tissue from the box and held it against her eyes for a second. Then she folded it neatly and tucked it into her blazer pocket. Her fingers still trembled and she grabbed hold of one hand with the other. She dug into the skin with her thumbnail, held it there, a small crescent appearing. She glanced up into the driver’s mirror. She had to eat.

Slamming the car door, she clattered across the sidewalk. An Italian restaurant blaring teen pop normally would have given Cynthia reason to doubt the quality of food. But she was not concerned with quality. She ushered herself in quickly, did not wait to be seated. “Scotch and water and a menu,” she said when her server appeared.

“What type of Scotch would you like, ma’am? We have—”

“Your best. And I’ll have some bread right away, focaccia or garlic bread, whatever you have … and a garden salad.”

“Shall I still bring a menu?”

“Yes,” she snapped.

The food was over-seasoned but warm. When she got this way, it didn’t matter. Forkfuls went in without acknowledgement. Her mouth and eyes filled with steam. If she noticed the server watching her from the back, she didn’t bat an eyelash. She was all gnocci, all bread and olive oil. She was swallowing, swallowing, swallowing. The brown swirl of vinegar adorned the plate three times, and Cynthia felt herself melt into its shapeless whirl.

A woman at the counter was acting very coy with the busboy. From where she sat, Cynthia could see the servers through the small rectangular window. One wall of the dining room was mirrored and, though she doubted anyone else could see, their positions were reflected to her. They were standing at the back of the kitchen, their hands traveling back and forth with a skinny white spliff, on which they both took turns. Cynthia piled her plates at the corner of the table so the busboy would come and take them. She glared at the dark-haired woman, whose small rump, upon the red bar stool, made a pinpoint like an exclamation mark out of her tight composed body.

The busboy was on his way back to the kitchen when Cynthia flagged him in the same mirror she had used to watch his coworkers. Cynthia saw the woman on the barstool observe their interaction, still coyly sipping from her wineglass through lips that left a dainty colored smudge.

The boy, who was perhaps twenty-four or twenty-five, tall and dark and wiry, approached the table. His thumb knuckle grazed her plate. She put her hand on his arm, waylaying him.

“What do I owe you?” she asked, her purse snapping open, a wad of bills there, appearing instantly in her lap.

He looked down at the money, sheathed from anyone’s sight inside the open mouth of the black silk change purse inside the black leather bag.

“Server …” he replied. He had an accent. She liked that.

She smiled, lopsidedly, a quivering finger going to her hair, which she wrapped around it, the long blond strand falling forward in a manner he would surely understand. “Where is your bathroom?” she queried him with an openly sexual smirk.

He gestured helplessly, his face a blank slate.

When Bonnie Brown-Switzel entered the ladies’ room, her ears filled with the sound of panting and shaking. The metal walls of the cubicles resonated with a strange savage music. The quiet grunting came from the third stall, bumping firmly against her ears. She had been about to let the door fall closed, but reached behind her and caught it, shutting it softly.

Without looking at the shoes beneath the pink partitions, she knew that it was the busboy and the blonde: a short, sharp woman with a Roman nose, pin-straight yellow hair, and powerful watery eyes, the kind of woman who held herself very upright in spite of her height and made Bonnie feel as if she should do the same. Bonnie had seen him go down to the basement after the blonde, a couple of rolls of toilet paper under one arm and a plastic gray key taped to a wrist-thick stick with Don’t Lose written on it in black marker. One of them was moaning—him, Bonnie thought—the other grunting. As they pitched against the side of the cubicle, the toilet paper dispenser mouse-squeaked a repetition of hips and tin, and Bonnie stood motionless in the doorway.

Slowly, she made her way along the wall, toward their hideout and into the stall next to them. The cubicle door closed of its own accord. As she set one foot upon the toilet seat, it wiggled. She paused—her heart hammering louder than any other noise she made—and then lifted the other foot up. The sound of grated breathing filled her ears. She held her breath. Crouching, she put her hand flat against the partition, and could feel the vibration of the two bodies on the other side. The exact spot behind where one of them was pressed naked.

Then the woman whispered urgently, “Not like that. Do it hard. Make it … make it hurt.”

“I can’t,” he replied, his voice thick.

Bonnie felt a heaviness welling low in her stomach, as it did when she had drunk too much coffee. She felt her head duck inside the feeling. She pulled her hand across her belly and leaned sideways, bracing her cheek against the thin makeshift wall that thrummed with them. Under the other hand, a heart was etched into the cubicle’s wall. Michael, it said inside it, though “Michael” would obviously never enter the ladies’ room to read it.

In another moment, the room filled with squealing, which was stifled, perhaps by a hand. It turned to a soft mewl, and what the man said was rough, in another language. She had no idea if it was vulgar, or if an “I love you” had fallen deafly between strangers. The scent of spring rose in Bonnie’s nostrils, the acrid airing out of things from winter. Over the soapy rose smell of the bathroom came a pungent, earthy aroma. Their bodies in motion. She imagined the places from which the smell seeped—from the boy’s pits, from his balls, from between the legs of the pin-straight blonde. Bonnie moved carefully to find a better position, leaned her forehead against the spot where she could feel them most, curled her fingers through her hair, and pulled it to keep herself silent.

Soon they stopped. He exhaled. Bonnie could hear the saliva in their mouths, ticking. There was the sound of shuffling. Buttoning. A belt buckle. A clasping of snaps, or was it purse lips? Then the woman said simply, “Thank you.”

The cubicle door opened and the skeletal wall shook beneath Bonnie’s cheek. She pulled her hair harder. The wooden door to the restroom opened and closed. He was gone.

In a moment, palms slapped the floor and the woman in the next stall began to wretch, vomiting violently. Bonnie shifted quickly, the squeak of the toilet seat concealed by the moist unpleasant wash of things going down the drain next door. The unzipping of a bag, and the woman had straightened. Bonnie could feel the weight as the woman leaned again against the wall nearest her.

A moment of cold-tile silence followed. The fluorescents crackled.

Then the woman on the other side began to cry, her sobs small and controlled, like stones thrown into a basin.

Bonnie waited until the door had opened and closed again and stillness stretched past 8 p.m. Then she tentatively left the cubicle, her face, in the mirror as she passed it, much as it had been that morning. She stopped to wash her hands, though she didn’t know why.

At home that night, as she lay in bed, her back pressed to Mr. Switzel’s ample stomach, his great arms wrapped plainly around her, thin rivers ran fr

om the corners of her eyes. She wondered where the boy had gone when he finished, what waited for him, what words he had said, and whether he would remember them later. She wondered if the woman lived alone. Mr. Switzel shifted, patted her thigh solidly, as if it were a cocker spaniel. Outside, she could hear the wind bubbling through the thin, decorative tree below their balcony. Three years, she thought, the length of time they had been married. Forty-seven years still ahead. It will all disappear, she thought. I will ruin it all.

SICK DAY

BY MARK SINNETT

CN Tower

Donny Freemont was just too damn disappointed to go on. It was as if floors had fallen on the inside.

He lowered his head and thrust his chair away from his desk, then leaned all the way back to stare fixedly at the stippled ceiling. It was ridiculous, he knew that, but there was no denying it had taken firm hold. He put the call through to his receptionist.

“But Mrs. Sanjit is already here,” Tina protested.

Donny squinted at the door, as if he might see through the bird’s-eye maple laminate that had impressed him so much when he signed on at the clinic two years ago. Then he concentrated on the hiss in the receiver, tried to match it to the space beyond the door, to Tina wriggling at her desk, and the line of molded cobalt chairs out there that he considered a grave mistake because they were flimsy and uncomfortable.

“Does she know I’m in here?”

Tina huffed. “She’s not an idiot, is she? She’s been here half an hour. You know how she is.” She lowered her voice. “She saw Mrs. Lawford come in and then leave. And I think she might even have been here when your one-fifteen left. Shit, you’re going to want me to cancel all those for you too, right, Donny? You have a full slate of appointments this afternoon. And you know I’m not going to be able to reach most of them, and they’re going to show up and I’m going to have to talk to them.”

Toronto Noir

Toronto Noir