- Home

- Janine Armin

Toronto Noir Page 22

Toronto Noir Read online

Page 22

“Do you think she can hear you, Tina?”

“Oh, now you think I’m the idiot.”

He stood at the window and waited for the all-clear. A half-mile away, a glass-fronted elevator climbed the CN Tower. Below him, a woman scurried diagonally across the intersection. Another woman shook out a yellow Shopsy’s umbrella and inserted it roughly into the bracket on the side of her hot dog cart. A light snow began. He tried (and failed dismally) to track the first flakes all the way to the ground.

He had glanced at the day’s appointments when he arrived. In addition to Mrs. Sanjit, he could look forward to Howard Desai and his grossly swollen prostate. And Timmy something-or-other, who needed twelve sutures removed from his forehead. There was Anne Davies, chronic, non-responsive depression, and ancient Hetta Jamieson experiencing another flare-up of her gout. Flu shots, blood work, and sore throats. Hardened lymph nodes that frightened the hell out of everybody. Well too bad, Donny thought. Today there was nothing he could do for any of them.

Safely out of the building, he headed north and then west along Queen. Turned up the collar of his wool jacket and burrowed into the afternoon’s cold shadows. He slowed a little beyond Spadina. He liked this stretch. The halogen-drenched tattoo parlors and used CD shops, the YMCA mission and thrift shop, the all-white design stores and so many restaurants: The Left Bank. La Hacienda. Citron. The Paddock, a few doors south on Bathurst. The last time he was in there— was it Thursday? Friday?—they had been playing the new Radiohead CD and Grandaddy’s The Sophtware Slump. He was pleased to recognize both those albums, particularly Grandaddy. It had made him feel relevant, it had made him feel young. His noting the way it made him feel was, he suspected, a sign that he was, in fact, not young at all, and was just clinging to the illusion of hipness because he haunted once in a while the “alternative” aisle at HMV. But he was mostly at ease with that. He believed that in all the important ways he could still pass for a man in his late twenties.

He ducked into the Stephen Bulger gallery. He wanted to warm up. A small vee of snow had gathered in the neck of his coat. He shook himself out, stamped on the welcome mat. The woman in the back room looked up from her work and smiled. They knew each other. Eleni had been at his wedding. She and Maria, his wife, had graduated from Queen’s University at the same time, both of them coming away with a degree in English literature. And now Eleni worked in this gallery and struggled with a first novel, while Maria worked at least half the year (or so it felt) in northern Ontario, scouting land for a reforestation company, each spring supervising a team of tree planters, setting up bush camps, keeping in touch with her husband via radio phone, meeting him in Thunder Bay occasionally for a rushed and never completely satisfactory twelve hours before he flew back south and she lit out once more for the logging roads.

“You missed the opening,” Eleni said. She indicated the walls. A husband and wife team had photographed human embryos preserved in formaldehyde, snakes curled in thickwalled beakers; fish crammed together and stacked heads up, like … well, like sardines. He saw at once that the colors involved were brilliant, alive; the work hummed. One of the fetuses seemed perfect, viable, and wore what was described in small black type as a Turkish cap. Next to it were another baby’s feet, severed at the shin, the cuts ragged and amateurish, the plump toes webbed. The photographs were mounted on sheets of half-inch acrylic which, Donny supposed, was intended to approximate the experience of viewing the original containers. “They were here,” Eleni continued. “The artists. Do you like them?”

He stood before huddled pre-infant polar bears, three of them, floating, with oversized velvet paws and hooked ivory nails, golden fur. But all he could think about was the damn music. The reason for his having fled the office and scurried like a rat along Queen Street. For his standing beside Eleni when he should be listening to the irregular heartbeat of Janice Wolcyk, while his wife, the adult, fulfilled her obligations and slept under a thin floral duvet at Thunder Bay’s Lakehead Motel.

“Who knows,” he said. And then he confided in her.

She took him to her desk, set him up with a glass of Pinot Gris left over from the weekend opening. She pushed aside assorted slides, black-and-white proofs of Italian industrial sites, a pizza box from Terroni’s a few doors down, and then sat on the edge of the work surface. She crossed one leg over the other and tugged at the thick, soft hem of her black leather skirt. She’s the doctor here, he thought bitterly. And I’m the patient. I am Sunil Desai with his strange rash. I am Angel Caddis with his night blindness.

“A new CD did this to you?” She seemed amused more than anything. It wasn’t very professional of her.

“I know. I know.”

“A bad song has you running away from your responsibilities. You have to be kidding. Are you?”

“Well, obviously it’s not really that. It can’t be.”

“What is it, then?”

“I don’t know,” he admitted. “I only know what triggered it.”

“A song,” she repeated.

“Right.”

“Jesus.” Eleni stared into the gallery as if ghosts were waltzing at its center. Finally she said, “I remember one of their songs.” She sounded wistful. She looked at him. “Well, I remember a lot of them, of course. But they were never really my thing. Too boy for me.”

“Which one?”

“In the video, he’s sitting in a bar, moving a glass of whiskey around gently. Singing. It’s really quite moving.”

Donny nodded. “‘One,’” he said.

Eleni reached out and touched Donny’s shoulder. She laughed lightly. “You’re right. That’s it.” She took back her hand. “And at one point he doesn’t sing along with the song. He just stares mournfully, as the words go on without him.”

Donny nodded again and she poured him more wine. She thinks I’m a sad case, he thought. Perhaps even that I need to be medicated. He held her gaze until she looked away awkwardly, into the gallery. She asked after Maria.

“She’s fine. We’re fine. It’s not that.”

He remembered the phone call he had made to Maria last night. It was late, past 11. The polls had closed hours before in the American presidential election, and the result was too close to call, he thought, but the networks had just called it anyway. There was a one hour time difference between him and her. It was enough that she might still be awake.

He was right because she answered quickly. She’d been doing paperwork, she said, and was glad to hear his voice, but asked if she could put him on hold. Before he could answer she was gone, and some quirk in the Lakehead’s wiring left him able to hear everything happening at the front desk. The receptionist fought off the drunken advances of two men on their way from the bar to their rooms. “When did she get off?” one of them asked. “Shortly after she comes up to see us,” the other one slurred, and the two of them cackled, thumped at the counter. When Maria came back on the line she apologized; she had been in the middle of a massive calculation: trees and hectares, hectares and trees. He told her what he’d heard.

“I know those guys,” she said. “They’re fucking assholes.” They were hunters, and in their orange coveralls you could at least see them coming, she said.

“Too bad the moose can’t,” he said morosely, and they shared a sad, distant-from-each-other laugh. “How much longer will you be?” he asked.

She didn’t know. “It depends. Whenever it snows, and if that snow stays on the ground, we’ll call it a day.” The TV flickered across the room and he told her it looked like the Americans were stuck with Bush, and she produced a sound that suggested to him a wince.

By the time he woke up this morning, CNN had retracted their initial election result forecast, and Al Gore had similarly retracted his concession. It was a shock. The future of the world had changed while he slept. Thrown, he beheaded two soft-boiled eggs and sat with them in the kitchen. Cholesterol be damned. He unfolded the Globe and Mail and began to read. Then it came to him.

He had bought the CD and hadn’t heard it yet. It was still in his briefcase. He found the bag in the front hall and wrestled with the wrapper. He slid the new disc into the player. The neighbors in the condominium below wouldn’t appreciate this at 8 in the morning, but he turned up the volume anyway, stopped at six and then nudged it past seven. This was his home. He could do that.

It began. The heart is a bloom, shoots up through the stony ground. He liked it.

He recounted this series of events for Eleni in the gallery. She had moved from the desktop into her chair. Poured herself some wine. She sat across from him and swivelled back and forth. It was good of her to indulge him like this. Since he arrived three people had come in and looked around. One of them, a woman in shin-high green suede boots, had looked over the price list and hung around expectantly, but Eleni had ignored her, which must have been hard. These photographs cost three thousand bucks each; it didn’t matter how good they were, they wouldn’t sell themselves.

“And then what happened?” Eleni said.

Donny rubbed his face vigorously. He knew he should extrapolate from what had happened rather than giving her the literal details. Interpret it. Physician heal thyself. He could do that, perhaps. Decide what it meant even as he began to tell her. Talk himself out of this dumb funk. But what he actually said was, “The second song.”

She leaned forward, put her elbows down on the desk, rested her chin on the hammock she made of her palms, and squinted at him. Donny thought she may even have closed her eyes completely.

“The rest of the album, in fact,” he said. He felt a need to shore up his case and thought that might do it.

“You don’t like it,” Eleni said. She spoke quietly.

Did she think he was crazy? Or merely pathetic. He was sinking in her esteem, getting himself crossed off all sorts of lists. The snow outside was gathering on the road now.

He ploughed on. “It’s shit.”

“So? Big deal.”

Donny shrugged. “I don’t know. It threw me. It’s thrown me. I feel strange.”

“Let down,” she said.

“I suppose.”

Eleni got to her feet. She smoothed the front of her skirt. “I can feel that wine,” she said.

Donny held up his glass. Eleni was moving away. She was in the gallery again. Maybe his time was up. She had run out of patience.

He apologized for coming.

She paused; she had been hasty and he could see that she knew it. She told him not to be stupid. “I love seeing you. But this … this music thing,” she said, “seems very small. I know it doesn’t feel that way to you, but …”

“I know.”

He felt about twelve years old. As if he had presented her with a broken toy. Like what had happened was apocalyptic.

He mumbled another apology that she said was unnecessary. She said they could talk about it some more if he liked, but he couldn’t do it; the room was too warm for him now. There was, inexplicably, too much of a contrast with the world outside. Strange that he hadn’t noticed it before. Eleni took hold of his elbow and smiled, tried unsuccessfully to hold his gaze.

When he pulled open the door to leave, a small silver bell on a brightly colored wool strap tinkled brightly. A woman in a long mink, clutching a gray-eyed poodle in a fitted red jacket, turned sideways to squeeze past him. Eleni would be pleased, he thought. Maybe not about the dog—he assumed that was something she would frown on—but this woman seemed to be in a hurry and she didn’t look at him. As he stood in the open doorway, she seemed to focus already on the polar bears. She wanted them; he felt he could discern that with certainty from the movement around him, the expensive scent he lifted from her as she headed in the opposite direction. He had diagnosed her intent, he decided. It was as real to him, as clear, as the flu.

He continued blindly along Queen, but after a block he cut up into Trinity Bellwoods Park and sat in the cold on a stiff and creaking bench. He wasn’t alone. Two old men conversed in Portuguese. One of them reached absentmindedly into a plastic bag and cast handfuls of breadcrumbs and rice onto the white path. He looked into the gray sky, watched as from the corners of it, from the furthest points, pigeons collected, swarmed, homed in on him. Soon the path was alive with them. They clambered over each other. Their golden eyes, storm-cloud wings.

Streetcars hauled themselves west. Men in plaid jackets scampered about on scaffolding behind siding that advertised two-story loft spaces. In the dusty doorway of a dilapidated store that seemed to be called Textile Remnants, a woman bulky with layered tweed overcoats arranged a bed of boxes and torn blankets. Hypothermia, Donny thought. Head lice. Schizophrenia. Absentee votes.

He needed to leave. He had arranged a squash game for 6 o’clock because he didn’t want to go home to an empty apartment. He knew that if he did, he would stand in the doorway to the kitchen picturing the contents of the refrigerator, taking inventory of the booze, wondering what to drink and eat and in what order. How much was too much? What constituted moderation for today’s stressed professional? How much did he weigh? Where the hell was Maria and when would she come home?

The pigeons startled at his rising. The Portuguese men with the bread eyed him suspiciously. It was cold; he had no reason to be here. His was a different language. He passed behind their bench rather than in front so that the birds would settle again. The rice blew about on the ground. But it wasn’t rice. He paused. It wasn’t bread either. It was some sort of animal fat. And maggots. The grains of rice were actually maggots. And the breeze had died. The creamy mass of them squirmed on the ground.

Donny was on the streetcar heading east. Back toward the towers, the winter noise and end-of-day hubbub. His squash game was in the basement of a hotel. He peered grimly into the failing light. The noise of the carriage, the electric click and spark of it, was comforting somehow. There was the atomic and tinny buzz of a Walkman behind him. The smell of french fries. But then, with a start, he remembered another patient: Adam Govington. Damnit! He had completely forgotten about Adam’s appointment.

Adam was going to die. And all of them—Adam, his mother, and his grandparents (the father lived in Denver with an accountant and had nothing to do with them, even now)—were going through the motions. They met to measure the rate of Adam’s decline. Donny thought the boy would be lucky to make it to Christmas, and there was nothing he could do about that. He was merely a middleman now. He relayed information from the specialists to the family; he interpreted the graphs, translated the jargon. And he hid the truth from them. The exact thing they came to him for, he denied them. Decided it was better this way—to deliver platitudes, to suggest things were slightly brighter than they really were. Adam could die any day. He was close. It was even possible he didn’t show for today’s appointment. Or that he wouldn’t last long enough to witness the final outcome of the American election, or the arrival of the storm system Donny had heard was gathering over the Rockies. He might miss the removal of the fiberglass moose that had cluttered Toronto’s streets and squares for months. Adam Govington now lived at the very edge of the world; he looked over his pale shoulder from the crumbling absolute brink. And Donny should have been there with him this afternoon.

Trouble was—and he panicked at the thought that this might be the real reason he had blown the afternoon off— Adam Govington’s mother had recently caught Donny looking at her thigh. His gaze had come to rest on it only in passing. But she had caught him. More than once. Donny had wanted to protest that it wasn’t even her thigh, exactly. The short stretch of leg between her knee and her thigh proper is what had fascinated him. What was that part of the body called? If anyone knew, he should. She had looked at him icily, evenly, for a moment. But then the moment passed and they were once again discussing her son. She hadn’t forgiven him exactly, just decided, Donny thought, that the world could still unfold in a more or less orderly fashion despite his fuck-up, and she should let it go. The doctor to your dying son could be competent and also,

at the same time, during the same appointment, a complete and utter asshole. Donny squirmed at the memory.

He collected his athletic gear from the locker at the hotel. It was getting stale; he would have to take it home after the game. Allan was already on the court, playing alone, darting enthusiastically over the hardwood. Donny waited for the ball to get away, to twist madly into a corner and stop, and then he opened the glass door and slipped inside.

Allan was a year younger than Donny and liked to pretend it made a big difference. “It’s not just that I work harder than you do to stay in shape,” he would say, “I’m also younger.” He was very tall, very thin, with a thatch of wheatlike hair that he kept short but unkempt. His eyes were green, his skin fair. But today, Donny thought, as Allan served gently into the corner and then loped after the ball, he looked a lot like an underfed wolf forced into a set of tennis whites.

They knew each other from the university. Allan was finishing a PhD in philosophy while Donny completed his residency. They would run into each other at the vending machines, slugging back terrible oily coffee, or hogging window seats at SpaHa, a university hangout. Now Allan ran an organic food shop on Adelaide. It was too far out of the way to make much money. Allan had thought that by setting up next to the fashion district he was guaranteed an imageobsessed clientele, but it hadn’t worked out that way. Still, it meant that he and Donny had kept in touch—the odd lunch together, or even a jog up to and around Queen’s Park, an occasional squash game and then a pint at the Wheat Sheaf or, if they were feeling more sociable, up two blocks at the Paddock on a Friday afternoon.

Allan leaned against the glass, bent over to catch his breath.

“Working hard?” Donny asked. “How long have you been here?”

“I closed up early.”

“Small world.” Donny collected the ball, squashed it in his fist. “I did the same thing. I had to get out of there.”

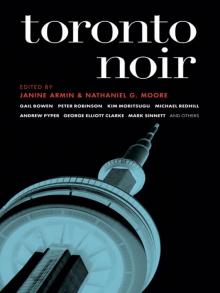

Toronto Noir

Toronto Noir