- Home

- Janine Armin

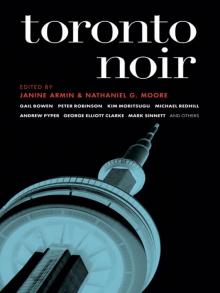

Toronto Noir Page 23

Toronto Noir Read online

Page 23

“The young soul rebels,” laughed Allan. He waved his racket in a way that was an indication for Donny to serve.

They rallied for a while without talking. Donny realized, not for the first time, that much of the pleasure he derived from these games was in seeing Allan struggle. He liked nothing better than to watch Allan tie himself up in a corner, his long limbs betraying him, or smack his racket against the wall in frustration, or come to a skidding halt on the varnished floor as the ball careened past him. He didn’t feel guilty about this; he was positive Allan felt the same way about him. Maria had come to watch them once and she was adamant she would never come again.

These gentle opening rallies were also a time when both of them strategized, planned their conversation. What did they want to talk about today; how hard would they push their points?

Donny suggested they get to it. He said he wanted to build up a sweat.

“You seem pent up,” Allan said, a little ways in.

Donny was winning. The score was seven to four. He held the ball way out in front of him, delicately, his racket pulled back. He looked over at Allan, whose eyes were fixed on the ball. Tension was evident in his thighs. “Pent up?” Donny said. “Pent?”

“It sounds odd when you say it, sure,” Allan agreed. “Pent suddenly seems like a made-up word.”

Donny served. The ball cleared the service line, but only just, then ricocheted into the corner behind Allan before he could lay his racket on it and died next to the glass. “Eightfour,” Donny said, pleased. That was his best serve. If he could repeat it at will, he’d give up medicine.

“So everything’s okay?” Allan tossed him the ball and held up a hand. He opened the door to the court and stepped out. He bent over the water fountain, in profile to Donny. The water rose up to meet his mouth in a weak glossy arc. Donny could see the individual bumps of his friend’s vertebrae through the thin white cotton of his shirt. When Allan reentered the court his chin was wet and he wiped it with his forearm, which also became wet. Allan pulled up his shirt and wiped his face with it. This was precisely how epidemics were spread.

Donny stabbed at the air with his racket. He felt the blood in him, a rush hour of molecules on the inside track. But then he paused. He thought of his patients. At home around their supper tables, telling their wives and husbands, their children, how their appointment had been cancelled, something about the doctor having an emergency. He thought of Adam Govington. He thought of Maria. Saw her vividly in her orange coveralls, making her way to the top of a slash pile, a drip torch in her right hand like a flaming scalp. Smoke in the air, moose hunters moving through the uncut trees at the horizon. He thought of Al Gore and George W. Bush sitting in their offices. The mass of thoughts in their heads. All of them, every one, had more right to be pissed off than he did. And yet he had acted the most dramatically. It was only he who had blown up.

Allan looked at him curiously. “You going to play?”

Donny served. It was a weak effort, the ball sailed on him, struck the wall near the point where it joined the ceiling and rebounded to center court. Allan pounced on the ball, smacked it dramatically at the bottom of the wall. It picked up a wicked spin somewhere in that series of events and bounded in a strange loop past Donny’s windmilling arm.

“I’m warming up,” Allan said.

Donny took the game comfortably and they began a second. They hadn’t spoken again. Actually, Donny supposed that couldn’t be true. He vaguely remembered Allan asking if he wanted to go again. And something about grabbing a bite. And Maria, how was she? They had swapped many words apparently, but none of them ran together to form what Donny considered civil conversation. He shouldn’t have come, he was still too screwed up. He thought of whiskey and of a newspaper article he had read that said any personality trait you had when you turned thirty you were stuck with for life. If you were a fuck-up at thirty, the reasoning went, then you may as well live with it, or shoot yourself, because the wiring was locked in. The article had annoyed Donny, probably because he was twenty-nine when he read it. He hated it even more now, because he had been unable to shed the memory. The more he tried, the more it cemented itself into the foundation of whatever process it was that allowed him to think. The brain was a mystery to Donny. He vividly remembered dropping a tomato slice into the sand on a trip to the beach with his parents when he was four years old, his father telling him to be a good boy and bury it. He remembered digging the tiny grave. But he couldn’t come up with, at this moment, the phone number for his own office.

Allan, though, was saying something.

“Say again,” Donny said. “I was miles off.”

“Nothing important.”

“It’s okay. What were you saying?”

“Really,” Allan said, “don’t worry about it.”

Their game was degenerating into a chore. Donny had derailed and needed to get back on track. He was taking out his middle age and his absent wife, and those dumb fuckers south of the border, and Adam Govington, on a pop band. And on a friend. Making them pay the price. After a moment, he told Allan he felt better. He could smell his own sweat, thought he could make out the sharpness of his own anger and frustration.

“But I didn’t say anything,” Allan said. He sounded a little disappointed. He wanted some credit and couldn’t find a way to take any.

They played a few more points. And then Allan said something stupid about Africa, how, if he went there, he would be really big, he could teach them a thing or two about getting goods to market. He combined the comment with a reckless overhead smash that through some complicated geometry sent the egg-sized ball arrowing for Donny’s face. He ducked and the ball hit the glass. Allan bent double laughing.

Donny, scowling, collected the ball from the ground and brought back his racket as if to serve before Allan was ready. The man was a gazelle, Donny remembered thinking afterwards, on the way to the hospital, not a wolf at all. The man could move when it really mattered. Because Allan responded to Donny’s feint by rushing toward the back of the court, head down. His intention, plainly, was to wheel around, make some miraculous return of Donny’s impending and unsportsmanlike serve.

Donny let the racket drop to his side. He moved a step to his right. Not enough to interfere with Allan’s progress, but enough to bring him within range. As Allan drew level, Donny spun and pushed hard at his friend, shoved him headfirst into the glass. The noise was unremarkable in these surroundings; players were always colliding with their environment. The injury rate was very high, but rarely was it anything serious. Allan, however, dropped as if he’d been felled by a hunter. A smear of blood on the glass, thickest at the point of impact, diminished as it approached the floor.

Donny gulped. He heard the gulp and he was, he felt, a cartoon of himself. He was two-dimensional, nothing was happening with the weight or import it ought to carry. This, instead of an act of murder, was the Roadrunner, it was Bugs Bunny. For a split second he even saw the animated figure suspended midair, just over the cliff’s edge, legs pedalling madly. He shook off the image and tossed away his racket, as if it were a gun. He dropped down next to the body, scraping his knees on the hardwood and depositing a touch of his own blood in that large cell with its begrimed picture window.

Donny had no doubt that Allan was done for. He touched his friend’s scalp gingerly, manipulated the loose mess of bone in there, the sharp edges and the soft bottom. Donny pushed. Yep, that was Allan’s brain. Resisting the fingertip pressure, but not well. It was an unusual consequence of an impact this moderate, but it happened sometimes. The skull could only take so much. And at only some angles. But hit it wrong and it was vulnerable as fruit. Great plates of bone could come free, float around under the skin. This had happened here. There was no coming back from this. It was simple tectonics; it was how the entire world worked.

He checked for a pulse and found one, but irregular and shallow. It was about what he expected. There was no hurry here. But there was, he

knew, protocol. He summoned the appropriate mix of panic and professional expertise, and had the boy at the desk with the towels call an ambulance. He jogged casually back to the court, where one or two onlookers had gathered. And then a couple more, who sat on the bleachers behind them as if this were all part of a game.

He identified himself to the paramedics. They exchanged curt nods. He explained what had happened, more or less, to a policewoman who wrote it all down in a small spiral-bound notebook.

“I have to change,” he told her, and pointed to his sweaty and blood-stained clothes. She nodded and Donny escaped to the locker room. He checked his BlackBerry for any messages he might have missed. There was something from Maria: Donny. Surprise! I’ll be home tomorrow. Can’t talk about it now. But the weather, you know. Anyway, I’ll call you later. Love you. And another from his office: Adam Govington had taken a turn for the worse, he was at the hospital. Could Donny possibly get in there for a consult?

Well of course he could. He was going that way anyway, wasn’t he?

The policewoman offered him a ride.

“It’s okay. I rent parking downstairs,” he told her. “I’ll follow you. If that’s okay.” He looked at her questioningly. There wasn’t anything else going on here, was there?

She said that was fine. But was he okay?

“I’m great,” he told her. “I’ve seen much worse.”

“He’s your friend, though. And they say it looks bad.”

Donny hung his head, as if shamed by her insight. “I’ll be okay.”

He climbed behind the wheel of his new Xterra. He was still on a honeymoon with this vehicle. It pleased him. Its height above the road, its not-quite-smooth ride and its smart sound system, its awesome roof rack. It made him happy. And as he climbed the ramp and turned on the headlights, filtered carefully onto King, checking the rearview, he realized he would have to be careful. He wanted to whistle a tune, but it would be wrong. It would arouse suspicions, and more than that it just plain worried him. It was inappropriate. Shit happened, he understood that. He hadn’t intended to do more than swear at Allan, tell him not to be so fucking racist, so damned superior. But there was little point getting excited about what had happened instead. He gave serious consideration to the notion that he was in shock. And that seemed quite likely. He took his own pulse, measured his breathing, put a hand to his forehead. Yes, he thought, that might be it. He probably shouldn’t even be driving.

He saw the ambulance some two blocks ahead. He couldn’t catch it. He slipped a CD into the player. Skipped straight to the last track because it was the only one worth listening to. Grace, she takes the blame, he heard. She covers the shame / Removes the stain.

The real reason for his calm occurred to him as he entered the hospital parking lot. It was about Adam Govington, all of this. With Allan dead, or damn close, Adam would get a reprieve. He was positive. That was the way it worked. It had to. You didn’t lose two people in one day. He had offered up Allan to appease the gods. A sacrifice. In return he wanted Adam back. Allan for Adam. It was a fair trade. More than fair. He pulled into a narrow space and found he couldn’t open the doors properly on the Xterra. He could have squeezed through the opening, but who was to say his neighbors would be as considerate. He backed out and searched some more. Because Grace makes beauty / Out of ugly things.

Donny panicked for a second when he recalled Maria’s message. How she was coming home. Which was great. But it wasn’t what he wanted. If he got something for Allan’s demise he wanted it to be Adam. He loved Maria, though he also wanted to watch that boy’s beautiful mother cry with gratitude. Why couldn’t he choose?

He found two spots empty beside each other and pulled in. He straddled the line. He turned off the engine and the music and sat quietly with his hands on the wheel. Relax before you go in, he told himself. It’s okay. It’ll all be fine. The gods know what you want. Those people in there don’t, of course, you’re not that obvious, you give off only a sense of goodness, a transparent wish that things turn out for the best for everyone. But the gods know. Oh yes, they do.

ABOUT THE CONTRIBUTORS

JANINE ARMIN writes regularly for the Globe and Mail and contributes to Bookforum and the Village Voice.

HEATHER BIRRELL is the author of I know you are but what am I? (2004). Her stories have been short-listed for Canada’s Western and National Magazine awards. “BriannaSusannaAlana” won the Writers’ Trust of Canada/McClelland & Stewart 2006 Journey Prize. Birrell also works as a high school teacher and creative writing instructor, doing all of this—barely—in Toronto’s West End, where she lives with her husband, Charles Checketts.

GAIL BOWEN learned to read from tombstones in Toronto’s Prospect Cemetery. Her books include A Colder Kind of Death, winner of a Crime Writers of Canada Arthur Ellis Award, A Killing Spring, and a series that includes The Endless Knot, the eleventh novel of which, The Brutal Heart, will be published in 2008.

GEORGE ELLIOTT CLARKE’S first novel is George & Rue (2005), an award-winning, critically acclaimed, true-crime story. His second novel, now in progress, is The Motorcyclist, a comedy of manners. “Numbskulls” was written in Banff, Alberta; Toronto, Ontario; and St. Petersburg, Russia (May– June, 2007).

RAYWAT DEONANDAN is a scientist, author, journalist, and professor. His stories have been published in seven countries and in six languages. He is the author of two critically acclaimed books of fiction, Divine Elemental (2003) and Sweet Like Saltwater (1999), which won the Guyana Prize for Best First Book. Ever indecisive, he divides his time between Toronto and Ottawa.

SEAN DIXON is the author of The Girls Who Saw Everything (2007), a novel about the last days of the Lacuna Cabal Montreal Young Women’s Book Club. He is also the author of several plays and a YA novel, The Feathered Cloak (2007). He lives and plays banjo in Toronto.

IBI KASLIK is a novelist and writes for North American magazines and newspapers. Her debut novel, Skinny (2006), has been translated into several languages and nominated for the Borders Original Voices Award and the Books in Canada Best First Novel Award. She currently lives in Toronto and her second novel, The Angel Riots, is forthcoming in 2008.

PASHA MALLA’S first book, a collection of stories, will be published by House of Anansi in 2008. He lives in the east end of Toronto, across the street from a prison.

NATHANIEL G. MOORE is the author of Bowlbrawl and Let’s Pretend We Never Met. He is the features editor of the Danforth Review and a columnist for Broken Pencil. He divides his time between Montreal and Toronto.

KIM MORITSUGU was born and raised in Toronto, and has written four novels set in the city: Looks Perfect (short-listed for the Toronto Book Award), Old Flames, The Glenwood Treasure (short-listed for a Crime Writers of Canada Arthur Ellis Award), and The Restoration of Emily (serialized on CBC Radio’s Between the Covers). She leads walking tours for Heritage Toronto, and teaches creative writing at the Humber School for Writers.

CHRISTINE MURRAY is a Toronto ex-pat who lives and works in London, England. She writes regularly for a number of Canadian and British publications, and is the editorial director of Ukula magazine and reviews editor of the Architects’ Journal. She is currently working on her first novel, an unlikely love story based in Toronto and London.

ANDREW PYPER is the author, most recently, of The Killing Circle. His previous three novels are The Wildfire Season, The Trade Mission, and Lost Girls. He is a winner of a Crime Writers of Canada Arthur Ellis Award, and his novels have been selected as Best Books of the Year by the Globe and Mail, the Evening Standard (U.K.), and the New York Times. He lives on Queen West, around the corner from a sign that reads, Hobos! Please Don’t Poo Here!

MICHAEL REDHILL is the author of five collections of poetry, four plays, and three works of fiction, the latest of which, Consolation, was long-listed for the 2007 Man Booker Prize and won the 2007 Toronto Book Award. He divides his time between Canada and France.

PETER ROBINSON is the author of seventeen I

nspector Banks novels, most recently Friend of the Devil, two non-series novels, and the short story collection, Not Safe After Dark. He has won numerous awards, including an Edgar, a Dagger in the Library, a Swedish Martin Beck Award, a French Grand Prix de Littérature Policière, and five Crime Writers of Canada Arthur Ellis Awards. He recently edited The Penguin Book of Crime Stories and he lives in Toronto.

EMILY SCHULTZ is the author of several books, including the poetry collection Songs for the Dancing Chicken and Joyland: A Novel. Her new novel, Heaven Is Small, is forthcoming from House of Anansi Press. She has lived in Toronto’s Parkdale for seven years and is not sure where she will do her laundry once the next condo tower goes up replacing her beloved Super Coin.

NATHAN SELLYN was born in Toronto. His first story collection, Indigenous Beasts, was short-listed for the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize and the ReLit Prize, and was the recipient of the Danuta Gleed Award for Canada’s Best First Fiction Collection.

MARK SINNETT was born in Oxford, England, moved to Canada in 1980, and now lives in Toronto. He is the acclaimed author of a collection of stories, Bull, and two books of poetry: The Landing, which won the Gerald Lampert Memorial Award, and Some Late Adventure of the Feelings. His novel, The Border Guards, has been published internationally in several languages.

RM VAUGHAN is a Toronto-based writer and video artist originally from New Brunswick. He is the author of eight books and a frequent contributor to numerous periodicals. His short videos play in galleries and festivals across Canada and around the world.

Also available from the Akashic Books Noir Series

Toronto Noir

Toronto Noir