- Home

- Janine Armin

Toronto Noir Page 5

Toronto Noir Read online

Page 5

The Silver Birch explosion had not only destroyed Lloyd’s house and wife, it had also destroyed his car, a silver SUV, and he wasn’t going to bother replacing it until he moved to Vancouver, where he’d probably buy a nice little red sports car. He still popped into the studios occasionally, mostly to see how things were going, and luckily his temporary accommodation was close to the Victoria Park subway. He soon found he didn’t mind taking the TTC to work and back. In fact, he rather enjoyed it. They played classical music at the station to keep the hooligans away. If he got a seat on the train, he would read a book, and if he didn’t, he would drift off into thoughts of his sweet Anne-Marie.

And so life went on, waiting, waiting for the time when he could decently, and without arousing suspicion, make his move. The policeman didn’t return, obviously realizing that he had no chance of making a case against Lloyd without a confession, which he knew he wouldn’t get. It was late November now, arguably one of the grimmest months in Toronto, but at least the snow hadn’t come yet, just one dreary gray day after another.

One such day Lloyd stood on the crowded eastbound platform at the St. George subway station wondering if he dare make his move as early as next week. At least, he thought, he could “go away for a while,” maybe even until after Christmas. Surely that would be acceptable by now? People would understand that he couldn’t bear to spend his first Christmas without Laura in Toronto.

He had just decided that he would do it when he saw the train come tearing into the station. In his excitement at the thought of seeing Anne-Marie again so soon, a sort of unconscious sense of urgency had carried him a little closer to the edge of the platform than he should have been, and the crowds jostled behind him. He felt something hard jab into the small of his back, and the next thing he knew, his legs buckled and he pitched forward. He couldn’t stop himself. He toppled in front of the oncoming train before the driver could do a thing. His last thought was of Anne-Marie waving goodbye to him at Vancouver International Airport, then the subway train smashed into him and its wheels shredded him to pieces.

Someone in the crowd screamed and people started running back toward the exits. The frail-looking old man with the walking stick who had been standing directly behind Lloyd turned to stroll away through the chaos, but before he could get very far, two scruffy-looking young men emerged from the throng and took him by each arm. “No you don’t,” one of them said. “This way.” And they led him up to the street.

Detective Bobby Aiken played with the worry beads one of his colleagues had brought him back from a trip to Istanbul. Not that he was worried about anything. It was just a habit, and he found it very calming. It had, in fact, been a very good day.

Not because of Lloyd Francis. Aiken didn’t really care one way or another about Francis’s death. In his eyes, though he hadn’t been able to prove it, Francis had been a cold-blooded murderer and he had received no less than he deserved. No, the thing that pleased Aiken was that the undercover detectives he had detailed to keep an eye on Francis had picked up Mickey the Croaker disguised as an old man at the St. George subway station, having seen him push Francis with the sharp end of his walking stick.

Organized Crime had been after Mickey for many years now but had never managed to get anything on him. They knew that he usually worked for one of the big crime families in Montreal, and the way things were looking, he was just about ready to cut a deal: amnesty and the witness relocation plan for everything he knew about the Montreal operation, from the hits he had made to where the bodies were buried. Organized Crime were creaming their jeans over their good luck. It could mean a promotion for Bobby Aiken.

The only thing that puzzled Aiken was why? What had Lloyd Francis done to upset the mob? There was something missing, and it irked him that he might never uncover it now that the main players were dead. Mickey the Croaker knew nothing, of course. He had simply been obeying orders, and killing Lloyd Francis meant nothing more to him than swatting a fly. Francis’s murder was more than likely connected with the post-production company, Aiken decided. It was well-known that the mob had its fingers in the movie business. A bit more digging might uncover something more specific, but Aiken didn’t have the time. Besides, what did it matter now? Even if he didn’t understand how all the pieces fit together, things had worked out the right way. Lanagan and Francis were dead and Mickey the Croaker was about to sing. It was a shame about the wife, Laura. She was a young, goodlooking woman, from what Aiken had been able to tell, and she shouldn’t have died so young. But those were the breaks. If she hadn’t being playing the beast with two backs with Lanagan in her own bed, for Christ’s sake, then she might still be alive today.

It was definitely a good day, Aiken decided, pushing the papers aside. Even the weather had improved. He looked out of the window. Indian summer had come to Toronto in November. The sun glinted on the apartment windows at College and Yonge, and the office workers were out on the streets, men without jackets and women in sleeveless summer dresses. A streetcar rumbled by, heading for Main station. Main. Out near the Beaches. The boardwalk and the Queen Street cafés would be crowded, and the dog-walkers would be out in force. Aiken thought maybe he’d take Jasper out there for a run later. You never knew who you might meet when you were walking your dog on the beach.

NUMBSKULLS

BY GEORGE ELLIOTT CLARKE

East York

I.

Bad men? No, not really. But they were no good. Or they were good-for-nothing ne’er-do-wells. Three goofs.

As one might expect, their childhoods were good for adult-only nightmares. Their parents were ratty in style and snaky by nature. Their dads’ mouths were only half-toothed: The rest had been punched or kicked loose and lost. Their moms had craved abortions, but, addled, had said, “Ablutions,” and had been served a lot of alcohol instead. Not as bad as thalidomide, but not helpful either.

The East Coast trio’s pernicious sociology provides only dismal insight into the disgusting episode of savagery perpetrated in East End Toronto last May. Not even the excuse of primitivism mitigates the horror and stench of the crime, the abomination the three Nova Scotians wrought.

The names of the ex-Haligonians—once sailors turned truckers, who had migrated to East York following their dismissals from Her Majesty’s Royal Canadian Navy—will not be forgotten by anyone alert to the reality of monsters. Bruno Bellefontaine, 25, Peter Purdy, 34, and Scott “Scalpel” McAlpine, 27, were turfed from the naval service because they were constantly sinking in rum. Disordered by drink, they disobeyed orders. The three tough guys, muscular bullies, made better boxers and wrestlers than they did seamen. They swore an oath to The Queen, yes, but they swore constantly at their officers too.

(Their officers had hoped to ship the trio to Afghanistan, to be shot down or blown up by the irregulars of the opium warlords. Unfortunately, as shipbound sailors, they would have faced little danger from either narco-terrorists or Islamist drug smugglers. Indeed, plenty of other Canucks were being dynamited and decimated, all without even an apologetic letter from The Queen, but it was quite impossible to ensure the same fate for the water-borne warriors.)

Following their jettisoning from Her Majesty’s service, just last September, the three men drifted into the hard-driving, high-pay trade of trucking. Wanting to “get the hell out of the lousy Maritimes,” where they were infamous for brawls and extra-toxic intoxication and for getting punched out in every grotty pub or murky tavern in which they exposed their mugs, they eagerly enlisted with Great Lakes–Atlantic Ocean. They began transporting goods among the spaced-out (distant) cities of Halifax, Montreal, Toronto, Windsor, and Thunder Bay.

The three boys loved the job, but could not steer clear of the sauce. They had the awful habit of spiking their coffee thermoses with Pusser’s Navy Rum. To drive, just a little drunk, was okay, for it kept them pepped up, making their rigs smoke nonstop from payload to payload.

Off the road, the guys bunked in Toronto. It was terrifi

c: not very French, not very English either. It was a fine place to unwind.

They found a three-bedroom apartment in the only affordable, near-downtown place left in Toronto: East York. The location nudged them, by a mile or so, a bit closer to the real East Coast, and they were only a few blocks away from a semblance of Atlantic Canada: the Beaches. (Yes, the burg was hoity-toity, but the sand was sand and the water was skyblue.) Their corner was Coxwell and Danforth: a critical mass of taverns, cafés, diners, and medical facilities, everything from hospitals to funeral homes.

(In fact, to pass the north-south artery of Donlands Avenue and bear east along the Danforth is to encounter a horde of cripples wielding canes, gripping walkers, or speeding motorized wheelchairs along sidewalks or across streets. Between Donlands Avenue and Coxwell Avenue, the Danforth is a parade of invalids, interspersed with exotic immigrants, including strays from Atlantic coastal Canada.)

One truly funky hangout for the boys was the Terminal Diner, so-called because it was, three decades ago, a veritable bus terminal. Its decor was walls of black-and-white photos of undying Hollywood idols: Marilyn, Jack & Jackie, Lola Falana. The ceiling boasted vintage record album covers. Marilyn could wink at the boys as they slurped an extra-creamy milk shake; if they looked up, they could see Doris Day, Sammy Davis, Jr., Frank Sinatra, and Harry Belafonte beaming down at their french fries and chicken burgers, as if they were actual deities who could (and did) provide blessings for such greasy, sugary fare. No matter, the Terminal Diner was a cozy site for ostentation, semi-private smoking, and low-toned, public fuming.

Bruno, Peter, and Scalpel also loved checking out the Racetrack Tavern. But the best entertainment in the whole world was to sit on a park bench across from the Toronto East General Hospital and watch obscenely beautiful nurses pass in and out in white stockings, coats, skirts, dresses, and shoes, to eye the most interestingly limping, wobbling, or staggering patients, ideally women, also make their way outside to smoke, inside to die; their spastic motions; their disturbed, yet ballet-like movements; their flounces and jerks rendered them haunting to the point of arousing obsession.

Then again, none of the East Coast truckers were consummately paired with ladies. No, their unions were weekend flings or weeklong traumas. Their primary commitment was to the road, the rig, the rigmarole of work and drink and chat and card games, not to dames, who were great to eyeball but could only bring bad luck and babies.

The guys liked their low-rise apartment building on Monarch Park. Its rent was manageable on their three paychecks, and it was, for Toronto, unusually clean of cockroaches. The super—a Sicilian workaholic—was almost a stereotypical housewife, the way he fussed over every nook and cranny of the building, purging it of bugs, getting rid of “low-life scum” of all sorts, clearing out the garbage, and mopping and sweeping as if this were the exterminating duty of a soldier.

The boys didn’t even have to trouble themselves about who used the “can” first, last, always: Their road schedule ensured they were seldom “home” together. However, when they were all about, they’d recall their Navy days, and go out and get shit-faced smashed.

They could don dark sunglasses anytime and cruise the Beaches scoping out the pointed erections of breasts—or even, if very lucky, actual topless nudity (legal in Ontario for a decade or more). Or they could jaunt up to the Plaza, at Victoria Park and Danforth, and try the fries at Burger King, pick up porn from the Adult Store, or, when weepingly sentimental, buy Newfie ballads from World of Song. Or they could hit the swanky section of the Danforth—Greek Town—and oil their throats with ouzo while salting them with lemony calamari.

Although the three lads could still drink to the acme of absurdity, they did not scuffle much now. In Toronto, unfriendly waitresses and waiters would simply summon the police, who were neither as forgiving nor as helpfully fanatical about fisticuffs as were the Halifax bobbies. Hogtown’s finest would simply wade into an orchestra section of fists, swing their batons like mad conductors, or taser discordant miscreants, and then hogtie offenders’ wrists as if they were closing up a garbage bag. Prison was a likely outcome of a Toronto to-do. After all, the Tories had thrown up a lot of jails during the ’90s and the first years of the ’00s. So it was better to sucker punch a foe in an alley and scram. Bruno, Pete, and Scalpel were awfully quick with the slick, dirty knuckle throw.

But the biggest difference between Good Toronto and all the smaller cities, including Allô Police Montreal, was the presence of many more “people of color” (as the newspapers said) and the extra-delicate women, a plush rainbow of dreams. The boys had gone to school with a black woman here, a yellow one there, but they had concentrated their adolescent, juvenile lusts on the Britannic brunettes, the Germanic blondes, the undecided Acadians. Yet Toronto expanded “poontang” possibilities exponentially, from the trim copper goddess in a sari to the golden divinity in a T-shirt and shorts. The truest benefit of the city’s multiculturalism was its cosmopolitan smorgasbord of potential sex partners. Even the local cable TV monopoly sang the praises of this cornucopia of copulation possibilities, serving up such titles as Chocolate Sticks and Vanilla Licks, Bollywood Busts and Hollywood Lusts, Asian Gals and Caucasian Pals … When the guys weren’t drunkenly veering their rigs between Gog and Magog, they were only stopping to view their hotel room TV screens, always tuned to a Cubist dazzle of body parts, an orgy of conjunctions and subtractions, plusses and minuses, as clear as the frank numerals of a tax return.

During his days and nights at home on Monarch Park, Scalpel would supplement his TV movie purchases by peering discreetly from behind the living room Venetian blind at the across-the-street neighbors, a piquant blend of Greek pater and Sri Lankan mater, issuing in a daughter, a teen delicacy of cocoa-butter tastefulness, a seeming satin smoothness of skin, black hair as jet and as long as licorice, two eyes as soft as sable, almond-shaped, and dark brown, and lips of a raspberry pink and strawberry plushness. She usually wore a Catholic uniform of uncomfortable (for Scalpel) brevity of skirt. Her couture was peculiar, if visually exciting, for her papa was Greek Orthodox, at least in terms of how his mother dressed (in comprehensive black, save for a strand of white pearls about her neck). In contrast, the neighbor girl’s mother was not a devotee of modesty, for she, like her daughter, kept her hemlines and heels high. She was also transfiguringly beautiful, vaunting skin that was pure, sensuous sable in color and imagined feel, contrasting nicely with the honey-gold appeal of her daughter.

From his vantage point behind the Venetian blind, Scalpel could survey the thirty- to forty-second passage of the daughter from the house, her quick step to either the corner store or the parental car. On one memorable morning, a blast of wind had uplifted the skirts of both mother and daughter, revealing identical underthings of white lace. French?

Scalpel’s surveillance was a private recreation, but he was also studious. He paid careful attention to the caramel girl and the chocolate woman (decidedly not a matron), to the extent that he heard the mother call the daughter’s name, Diva, and the husband call the wife’s name, Godiva. Then he spied a story in the Scarborough Reflection, wherein Diva Galatis was front and center—color photo and surname—because she had won her school’s trophy for most valuable athlete, in field hockey, for the second triumphant year in a row. The photographer didn’t seem to care that Diva’s white bra gleamed through the pink threads of her tight top, along with the pointed suggestion of her curving femininity, but Scalpel cared. He kept the newspaper page folded in his wallet.

Come one special April dawn, Scalpel, the dark-haired, bespectacled, and solidly huge (but not fat) man, was padding along the sidewalk of Monarch Park, heading home from the Coxwell subway station, when he saw Diva, winsome in sneakers and womanish short skirt, stepping nonchalantly in his direction. His heart howled such thunder he was sure she would hear it and denounce him as a deviant. But no, she glanced at him, pursed her lips as she blew and cracked a bubblegum dirigible, smiled wanly, and said,

“Hi.” She was the epitome of curves. Scalpel could only mumble, or nearly moan, his reply. Immediately after she passed, he turned around and was greeted with the sweet vision of her plaid skirt swishing across her scrumptious derriere.

Thus, his surreptitious flirtation continued. Even Scalpel’s two eighteen-wheeler mates, Bruno and Pete, were ignorant of his lurid, selfish panting after Diva, this angel goddess who commandeered his fantasies. And life went on.

II.

Then struck calamity: Diva, the immortally beautiful (and probably virginal) woman was felled in the middle of a game by an uplifted field hockey stick that hit in pure, malicious chance against her skull. The blow had enough force to kill her instantly, but somehow not enough to scar or bruise her soft tender skin; Diva had dropped where she stood, in the exact instant of an additional triumph, in her sneakers, red-and-green plaid skirt, and white knee socks.

The death of the athlete, only eighteen (her whole life and its eventual decline now void), became principal news on TV, radio, the Internet, and even on the front page of the Toronto Star. East York Holy Angels High School announced a full day of mourning presided over by grief counselors, who would painstakingly explain that death could befall even a popular, good-hearted, and good-looking athlete—even a teenage one. Yes, no one was safe.

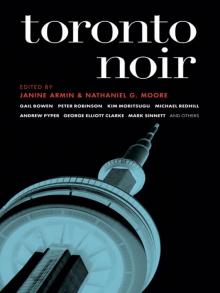

Toronto Noir

Toronto Noir