- Home

- Janine Armin

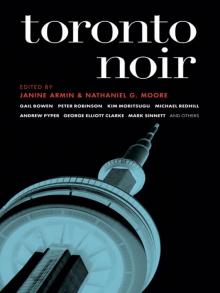

Toronto Noir Page 6

Toronto Noir Read online

Page 6

But Scalpel was personally broken. Not decimated, devastated. He felt he’d given his granite heart to Diva, and now she was gone, and he’d never touched her, never felt her. He’d merely breathed in her direction, and, at that moment, he’d been breathless.

Pete and Bruno found Scalpel in the dark apartment, a bottle of Tito’s Hand-Made Vodka handily half-empty and their buddy slobbering, slurring his words, reducing them to spit. He was moaning, moaning, “Diva was really, really, really unique.”

They wondered who this mystery lady was, this inspiration for their pal’s epic drunk. Scalpel drooled out his explanation, and his mates became intrigued. They too had noticed, now and then, the high school gal’s succinct skirts that didn’t so much cover anything as hover tantalizingly about. And they had also noticed Diva’s extraordinary features and had, quite involuntarily, grunted inside their own minds. Being whitebread boys, they mused normally about the pale, anorexic waitresses and big-mouthed, big-assed, whey-faced whores and the wholesome, buxom, pie-faced cashiers at Tim’s. Usually, they only vaguely appreciated the hot, ice cream–like colors of the “foreign hers.”

But Scalpel’s grief brought them, not to tears, but to lust for the dead neighbor, the Cinnamon Virgin of the Spice Isles. What could she have been like?

Pete studied the cute face in the obituary section. Diva did not belong among all the black-and-white oldsters slain by one casual cancer after another, whose mourning relatives (publishers in this case) all forbade flowers, desiring that sorrow be totaled in the form of a tax-deductible donation to a medical research charity. Diva glowed in full color, brilliant enough that her face seemed to lift from the drab newsprint and illuminate the room. Pete felt moisture in his long dried-up tear ducts. It was hard for him to believe that this fresh-faced chippie was lying waxen and cold in a mahogany chest in the Toronto East Funeral Chapel. Yet there were younger faces on the page too, and there was even a write-up about an unfortunate infant.

As Scalpel rocked and sobbed and wept into Bruno’s chest, Pete opened the cold beer and began to gulp it down. What was to be done?

He was not moved by altruism. When charities knocked on the apartment door, seeking money to stop the polar ice caps from melting, or to buy polar bears better food, Pete enjoyed lecturing the do-gooders with this tale:

“A woman’s German shepherd expired, and she wanted to take the corpse to the SPCA for disposal, but she didn’t have a car. She called every cab company in the city to find a driver to take her and her dead dog to the pound. But every cab company—all of them superstitious—refused, often rudely, to help. The poor lady had to sacrifice her best suitcase, cram her dead dog Daisy inside, and take the subway over to Yonge and Queen. Climbing up the stairs to the street level, she was huffing and puffing and sweating like she was raining. A man approached her and offered to help her upstairs with the case. She smiled and accepted. After hefting the suitcase up one flight of stairs, the man stopped and exclaimed, ‘Hey, lady! This suitcase is real heavy. What you got in here?’ She didn’t dare admit that it was a dog, so she lied: ‘Oh, just my old computer.’ The man grinned, and with instant vigor, bolted up the last several steps and ran off with his imagined booty.”

After concluding this saga, Pete would swing the door shut in the faces of the Latter-day Saints, the Witnesses, the Greenpeaceniks, and even the collectors of money for Little League baseball uniforms. What he’d never say was that he was the man who’d stolen the useless corpse of a dog. He was no charitable son of a bitch. But Scalpel was his friend. And the dead girl was, well, a tartlet, who would now be devoured by worms, a most criminal and dismal rape. Simple, crude animals would munch all her loveliness, snacking on eyes, ass, everything soft and vulnerable. This truth seemed to Pete suddenly intolerable and royally vile. He had seen her once, up close, her long black hair cascading over a white blouse, and he had felt lust polysyllabically sully his heart. How could this beauty be permitted to break down into loathsome slime? The strange impudence of maggots should not prevail where a man can frustrate their insults. Innocence topples to the tomb as easily as vice—this was a truth as unpleasant as a dirty rag. Something had to be done.

Pete felt repulsed by Scalpel’s panting, his tearful ejaculations, his blunt weeping, his vodka-addled fanaticisms, his clumsy hysterics. His friend’s liquored-up agony required a succession of vodka shots—but also a deed so nude in meaning as to be unprintable. Pete planned a Gothic and gay catharsis to mollify Scalpel’s drunken grimness. He felt a twinge of revulsion at his own idea, thinking, I am a bad man. I am the wrong man. I am a natural man—the worst type. Pete then communicated his scary amusement to Bruno, his shoulder wet with Scalpel’s tears and snot: Time for relief from (and for) their sad-sack pal. The trio could have a riot …

III.

The entry was not fastidious. The three men were burly, and Pete’s practiced crowbar jimmied open a basement window as easily as giving a teat to a baby. And just like they suspected, the sign in the window advertising The Police Alarm Company was fake—i.e., a lie. Not even a Toronto funeral home feared robbery.

Worried about a potential guard dog, Bruno took the crowbar and he swung it a few times, just for the feel of how it might waste a violent canine. But no saber-toothed poodle showed up.

Pete’s flashlight transformed the trio into three ghouls, but soon they had ascended from the musty basement—the warehouse of caskets, including some needing repair—and broken out onto the main floor. They made their way carefully to the viewing rooms and began cracking open the coffins, one by one, to see where Diva lay. The blubbering Scalpel got sick, throwing up vodka-scented spit over the plushly carpeted floor and onto the cuffs of Bruno’s pants. The big man wanted to slug Scalpel, but he simply snarled, “You’re such a fuckin’ slug.”

Scalpel shrugged. He couldn’t help feeling sick. One of the coffins they had just pried open was that of a blonde-gray woman, fiftyish. The problem was, in the flashlight’s concentrated beam, the cadaver resembled his mother. Logically, he knew that this corpse was not her, for she was still kicking up her heels, so to speak, with her second hubby, in Come-by-Chance. But, emotionally stricken, he had to vomit.

Two false starts on, the boys found the gleaming mahogany, one-room place that was Diva Galatis’s last redoubt on the planet. When Bruno pried up the casket lid like an unholy deity reviving—but not repairing—the dead, a gasp seized in all three throats, mouths, and lungs: The girl was awesomely beautiful, and the magic of makeup and preservatives had merely enhanced her natural perfection. She seemed to have simply walked off the street, stepped into this miniature bed, and gone to sleep. Blissful. Her funeral dress was simple, a white silk sheath, with discreet pads cupping the perfectly circular, if yet immature breasts. Her gold flesh shone through the filmy white of her grave bridal dress. Diva’s hands were set to hold flowers at her chest, and the brown fingers flashed brilliant magenta nail polish. Her almond-shaped eyes were closed under dark-almond-colored lids, and the eyelashes were lustrously sable. Her slender legs tapered down to white schoolgirl socks and flat-soled black shoes. Death was an obvious crime in this case.

“Feast your eyes there, bud!” Pete croaked at Scalpel, whose porcine hands were now stroking, with the most delicate delicacy, the fine, though cool, cocoa-tinted skin of his beloved, his desire, his child-bride, only fifteen years his junior. No-nonsense Bruno, a man of practicality, tore free the satin lining the girl lay upon and, encasing her in this material, lifted her, with little strain, from the box, with Pete holding her legs straight, while Scalpel, disbelieving his joy, tore off his jacket and set it on the floor, as an act of homage for the gently descending corpse. Now, holding the flashlight, Scalpel watched as his two friends arranged the woman, still in a state of fine repose, upon the floor, using the coffin lining as a makeshift bridal suite sheet, while Scalpel’s jacket was bunched into a pillow.

Bruno and Pete pried at Diva’s legs, which parted stiffly, wafting the in

sidious smell of formaldehyde. The two men rolled up her dress, revealing a flawless anatomy, including a nicely wispy black brush of hair at her sex.

Excited, Pete snatched the flashlight and yelled at Scalpel, “DO it! DO it! We ain’t got forever!”

Scalpel felt queasy, but Diva looked delectable. His desire overthrew all scruples. Besides, with a big-hearted laugh, Bruno was tugging down Scalpel’s pants, and then encouraging him to kneel before the prone treat. Scalpel surged—he felt his blood and flesh surge—forward. Next, he realized Diva’s smooth, cool thighs against his hot, hairy ones. Now he felt for the sex of the dead girl, believing that she would be kindly tight, if dry, and exquisitely gripping.

Bruno hollered, “Get her wet, boy!”

At this moment, Scalpel withdrew while Pete anointed the cadaver’s unblemished sex with drippings from a flask. It gleamed; the whiskey glinted.

Ready, Scalpel thrust himself into the corpse; it shook and jiggled coldly upon the floor. But a pathetic delirium gave him pause: He understood that he was raping his beautiful neighbor, this luxurious pinnacle of womanhood, even as he adored the whiteness of his manhood as it drove into the inert brown once-woman, in a parody of copulation.

Pete reveled in this cocky farce, this murky but arousing debauch. The girl was sweetly akimbo, and utterly pretty, but Scalpel was jiggling and wriggling and snorting like a swinish monkey. No, Scalpel was like a busy eel, spasmodic, darting in and out of the unexpected luxury of the virgin spoil, until his nasty, brutal sallies should attain their vain objective. Suddenly he was groaning. Pete spat icily, “Don’t cuss the chill! Pal the gal, man, and laugh.” Pete stared, as if drooling at the seesawing transports of his buddy.

After five crazy minutes, a climax shook Scalpel and he fell away from the icy doll. He was satisfied, but sobbing, then vomiting under the empty ripped-up casket, still held up at chest level upon its trolley.

Pete growled, “Sloppy seconds for me!” After some perfunctory cleaning with tissue taken from the nearby washroom, he was also soon moaning, “Diva, Diva, Diva,” as he writhed and shivered. How memorably thrilling it was to have this highly polished cadaver, this ready-made, unblushing, yet virtuous excellence!

Looking, still weeping, at Pete’s infernal coupling with the dead girl, Scalpel knew it was not devotion, but desecration. Pete’s insistent, unstinting strokes, executed not an ordinary vulgarity, but a fantastically monstrous treason— like someone befouling the face of The Queen with a bodily emission. Scalpel regretted his own too-immediate yielding to Pete, for the dude was grinding into Diva as if she were a pencil sharpener. Scalpel sulked like an emperor forced to accept democracy. Okay, so none of us are Christ! Does that mean Pete has to play a cockroach? Scalpel imagined only one remedy for his escalating distaste for Pete’s violence: hatred for the man himself. Diva’s ravishing would have to prove costly. Scalpel could not let the snake dump his venom into the defenseless girl.

Immersed in Diva’s swank vise, Pete felt like an opulent Vandal sacking Rome. This defilement was delirious. He thought, I am dreaming. I am desiring. I am bad. He was a phallic angel—no, a reckless devil—now building up to an inevitable nicety. Athletic, untiring, he steadily pumped away at the cold woman’s core, that moist gleam in the cylindrical light showing up his dark driving. It was a signal plunder, though the victim was as sticky as mud. A billy goat stench, Pete’s, hovered over the scene.

Still shadowy, beyond the flashlight beam in Bruno’s hand, Scalpel stealthily retrieved the crowbar and struck wildly but heavily at Pete. The iron bar swung. One blow would pulverize Pete’s petal-soft skull.

Bruno saw a long, black object sweep down into the white flashlight illumination and sink, cracking, splashing, into the crown of Pete’s head. Bruno did not even have enough time to let the flashlight shake or flicker as some black liquid shot from Pete and dirtied his own face and clothes. Bruno felt rueful, but Scalpel had been ruthless.

In an instant, Pete went from fornication to celibacy. A sizzling convulsion. Black gore pissed up from the pointedly indented skull. Ominous. Here is real bullshit, some real horse manure, Bruno thought.

Bruno switched off the flashlight just in case Scalpel wanted to take a swipe at him with the bloody bat. He wasn’t sticking around. He dropped the light and hauled ass back to the basement stairwell.

Freaked out by the murder of his buddy, by another buddy, because both had copped with a corpse, and shaking anyway, Bruno lost his footing on the dark stairs. He pitched into the void and came up twisted, his neck broken.

Not the type to quail before a dog’s breakfast of a crime, Scalpel retrieved the flashlight, and, in the dimming beam, pulled Pete off their victim and pushed his pal’s body into the drying vomit under the dolly hoisting Diva’s gutted casket.

Now Scalpel held Diva’s head on his lap. The girl remained for him perfectly pure, despite her bloody, ruined dress and the outrages lately visited upon her otherwise preserved perfection. His pitiful tears rendered hers beautiful.

FILMSONG

BY PASHA MALLA

Little India

The door of the Taj opened and two men came in. They moved past Aziz and stood at the sweets counter in the back. The only other customer was some old guy waiting for a take-out order. He was sitting at a table near the door, watching Gerrard Street through the window. It was close to 6 o’clock and getting dark. The streetlamps had come on and cars flashed by hissing through the slush with their lights on.

A young girl was working. Thursday nights were quiet. It was just her up front and her mum cooking in the back. She glided over and leaned her elbows on the counter.

“Ras malai,” said one of the men.

“With saffron,” said the other.

“We don’t do them with saffron,” said the girl. “Sorry.”

“What the hell, don’t do them with saffron,” said the first man. His voice was loud now. “First it’s minus bloody twentythirty degrees in your country. Benchod, you freeze your bloody nuts off! Now we ask ras malai with saffron, but you say no saffron.”

The girl whisked a stray bit of hair back from her forehead. “Yeah, no saffron. We’ve only got plain. You should try the gulab jamun. They’re good. Really fresh.”

The second man whispered something to the first man. Aziz scooped rogan josh into his mouth with his fingers, but didn’t take his eyes off the two men. They were dressed similarly: collared shirts—tucked into their jeans and unbuttoned to reveal great thrusts of chest hair—and leather jackets. The louder one had a mustache. The other didn’t. They both wore red threads tied around their wrists.

The second man, the clean-shaven, quiet one, said, “Gulab jamun, too sweet.”

“Try the jalebi,” said the girl.

The first one made a noise. “Benchod, even sweeter! You have ras malai, you add saffron, not too sweet. We want not too sweet.” He turned to Aziz. His eyes went from Aziz’s face to a poster above the table where Aziz was eating. On it was the actor Shahrukh Khan, mugging for the camera in sunglasses. “Is it right, Shahrukh?”

“Sorry?” said Aziz.

“Come on, Shahrukh.” He was getting into it now. “You want sweets, Shahrukh? You’re a film hero, which sweets will you order? You eat jalebi?”

Aziz looked at the girl on the other side of the counter. She looked back.

“Um,” said Aziz.

The two men advanced toward him. “What, Shahrukh?” said the one with the mustache. “Come on, yaar.”

The other one said something in what Aziz guessed was Marathi. Both men laughed. They were at his table now. The loud one poked his tin plate with a fingertip. “You eat meat, Shahrukh? You are Mussulman, just like the real Shahrukh?”

Aziz glanced down at his plate, at the half-eaten lamb. He looked up at the one man, then the other. They leaned toward him. There was beer on their breath. When the one with the mustache breathed his nose made a whistling noise.

Then a bell rang from the ba

ck. “Chicken tikka, naan, mattar paneer,” called the girl.

The old guy at the front of the restaurant got up. Aziz and the two men watched him move past their table and collect a paper bag from the girl. “Thanks,” he said.

The old guy left. Outside the snow was blowing in golden squalls in the light of the streetlamps. The two men turned back to Aziz. “Shahrukh,” said the loud, mustachioed one, “we are looking for a journalist. Do you know this journalist? His name is Meerza.”

“Shahrukhji,” said the other, “we work for a Mussulman. In Mumbai. We are not communalists. Our friends are Mussulman, Parsi, Hindu, Jain, Christian, whomever.”

The two men sat down across from Aziz. “I am Prem, this is Lal,” said the one with the mustache.

“Do you know this man, this Meerza?” asked Lal. He pulled out a photograph and slid it across the table. Aziz looked at the image. It was his neighbor, smiling before a typewriter. Aziz knew this man as Durani, the name written on his box in the building’s mailroom, and not Meerza. “We are journalists also,” said Lal. “We have come from India to meet this man.”

Aziz stared at the photograph. Once he had locked himself out and Durani had taken him into his own apartment until the superintendent arrived. The place had been empty except for a mattress on the floor and a few piles of books. While they were waiting Durani had prepared chai in the Kashmiri style, with almonds, cinnamon, and cardamom. Aziz had said nothing about this, nor had he mentioned the many books of Urdu poetry stacked around the room. The building, just west of Greenwood, was the sort of place where everyone had left a story behind somewhere else. The residents shared this, along with the understanding that no one needed to stir them up here.

In the photograph Durani looked different. There were no bags under his eyes. The skin on his face seemed less sallow. He appeared gregarious and happy, full of energy. His shirt was clean and freshly pressed. This was not how he looked now. But it was him.

Toronto Noir

Toronto Noir